The Origins of the Democratic Party (Part V): From the Wildfires of Zhejiang to a Nationwide Blaze

作者:朱虞夫

编辑:胡丽莉 责任编辑:罗志飞 翻译:鲁慧文

杭州的民运之火随着夏天的来临而不断升温,王有才一次次的抓抓放放,使许多来访者分头找到我们几个老民运的家里来。我印象比较深刻的是在酷热的烈日下,殷蔚红踩着克朗克朗响的破自行车,满头大汗地来回奔波;王培剑也经常过来给我讲讲组党方面的法律问题;徐光携夫人黄晓航抱着新生婴儿来我家,带来他的文章《抓不完的民主党人》,看到他们把那么小的孩子带出来,我心里很佩服这对年轻人的勇气;北京的艺术家严正学先生也是冒着酷暑来到杭州找到我,我将他带去王荣清家,后来严正学告诉我,王把他卖给了警察。刘贤斌与一位记者朋友也在那个时候来杭州,因为我不熟,就在他们面前很少说话,以至于那位记者以为我是个沉默寡言的人,而滔滔不绝的祝正明却被她记下许多不便公开的言论,使他十分恼火。

-rId2-1280X960.jpeg)

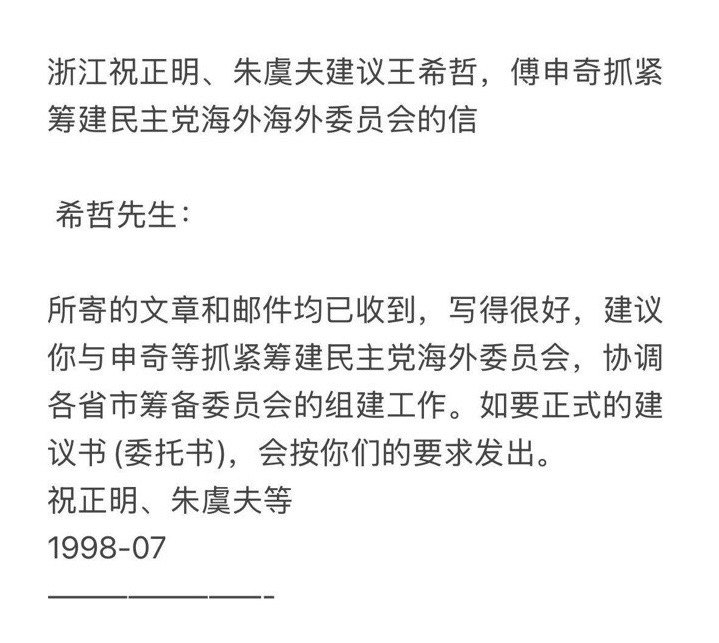

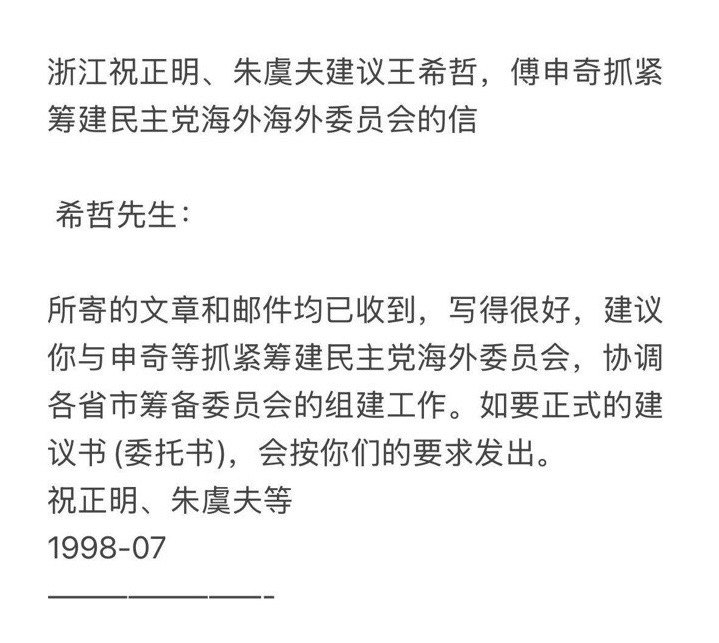

1998年酷暑八月,严正学来杭州,左起前排张玉祥、严正学、朱虞夫、王荣清,后排祝正明、毛庆祥。

1998年6月组党的消息传开之后,各地的许多民运人士来杭州考察“取经”,并希望我们能去各省“传经送宝”,把中国民主党热热闹闹的搞起来。大家碰头的时候就聊起了派人去各地“点火”,把各省民主党建立起来。吴义龙自告奋勇,说大家都走不开(有上班的、有做生意的),他刚把硕士论文交上去,最近没事。大家都同意了。

于是,大家一起筹钱给他作路费,列了各地方要找的民运人士名单和地址(当年组党运动兴起前,中国民运是“签名运动”,出了某时事事件,写一篇文章,大家都来签名,所以大家都留下了联系方式)。我们将各地的活跃人士找了出来,印在一张纸上,让吴义龙每到一地,按图索骥。出资的人,王荣清负担大头,其他人也都尽力凑上。一直在杭州积极参与活动的姚遵宪表示愿意陪着吴义龙一起去跑(事后知道这一路的食宿都是姚遵宪买单的,二十六年后,杨海还提起,当年吴义龙是坐飞机去的西安。但是吴义龙从来没有和我们提起过)。四川刘贤斌和湖南谢长发、西安傅升、辽宁唐元隽和冷万宝、重庆、黑龙江、甘肃、云南、广东朋友都先后来过,武汉秦永明是毛庆祥的老朋友,大约98年七月底由毛陪着一起去。那天毛庆祥从武汉回来告诉我,他们到武汉热得不得了,找到秦永敏的时候,秦在他卖煤气灶、高压锅零件的摊位上午睡,摊上放着一只传真机(秦当时在办《人权观察》),把秦叫醒,建议他一起搞民主党,秦一口就答应了,并立刻筹建了中国民主党湖北筹委会。

中国民主党浙江筹委会这个名称是经过仔细考虑的,王有才当时是个比较豁达的人,对名利很淡泊,鄙视追求个人权力,所以他搭建这么一个平台,平等对待各省的筹委会,让大家都来唱戏。只是王有才不赞同我搞街头政治,随便让“阿狗阿猫”都拉进民主党里来,他认为社会上招聘员工都有门槛,参加民主党怎能没有门槛呢?其中我最受大家诟病的就是,我把王荣清拉进民主党里来了,因为大家都认为他曾经在民主墙时期与公安一处合作,出卖过朋友。是的,我对此也是非常无奈的,毕竟草创的民主党有许多事要做,却缺乏做事的人,我搜罗扒剔,鸡鸣狗盗都需要。对于浙江自称是“中国民主党”的浙江筹委会,为其他省市的筹委会留下发展空间的做法很受大家欢迎,浙江不占山为王的谦卑做法使各省民主党踊跃建立,蔚成风气。

后来,从王希哲处,我了解到,海外后援会一直在不遗余力地推动各地的组党活动,他们尽力为各地购买传真机,为各地解决遇到的各种困难。

吴义龙在行程中也遇到尴尬时刻,九八年8月底,他找到北京某大佬家,对某说,希望某也能在北京成立民主党,某谨慎地对吴说,我们到里面谈。到里面,某对吴说:“你们要我搞,可以,我的位置怎么放?”吴愣住了,这个问题使他猝不及防,他是被派来“点火”的,不是来找个“主席”的,就在那里尴尬地笑。某一看没戏,就下了逐客令:“你去吧,我不搞!”天气酷热,吴义龙满身汗湿,央求某让他冲个凉再走。某把吴带到淋浴间,吴却长时间没完,某不放心进去看,吴的内裤挂在卫生间门把上,破的像渔网,某就干脆拿去扔了,挂上一条新内裤。吴沐浴完找不到内裤了,就大声喊。某让吴穿上那条新内裤。后来,因为吴义龙讲了找某大佬组党未成的事,某感到很不体面,就曝光了这内裤的事,某当时有句话是:“吴义龙这小流氓与我玩,我玩得他找不到内裤!”也算是在严酷日子里的一点轻松花絮。

从某家出来,在走访名单上找到任畹町的地址,去找任,任二话不说就组建了中国民主党北京筹委会,并在9月17日向北京民政部门提交申请。撵走吴义龙后,某大佬立即公开发布了他的“多读书、广交友、缓结社”倡议,但似乎响应的人不多,大家对组党的热情更高。在全国各地陆续公开组建了二十几个“筹委会”后,某大佬坐不住了,11月6日,要召开“中国民主党第一次代表大会”,一个提倡“缓结社”的人出来摘桃子,自然遭到以浙江为首的几乎所有民主党人的反对。终于他“要走在全国朋友的前面”,在11月9日搞了一个“中国民主党京津党部”自任主席,七个人封了六把交椅,任命了三位副主席,其中一位是天津的吕洪来。其时,吕洪来正在杭州做水果生意,需要杭州朋友帮忙,大家都去了。我问吕,你这个“副主席”怎么回事啊?”吕说,“老某这个人啊,就这个脾气,也没和我打个招呼,就把我的名字写上去了。”某大佬是第一个反对成立中国民主党的人,这些事实,当时都有公开记载。某拒绝搞民主党,又反对不成,召集了几个人,在11月初也打起了“中国民主党”旗号。虽然凑了“京津党部”,各地的“筹委会”没人买他的帐,于是他又心生一计,对秦永敏说,搞“筹委会”的太慢了,要马上成立全国党部。

几天后,某大佬在北京成立了“中国民主党全国联合总部”,浙江一直是他的眼中钉,某给我打电话,说他已经组建了中国民主党全国联合党部,他任主席,准备二个副主席,一个是秦永明,因为你们浙江是首先组党的,给你们浙江留一个位置,限你们在二十四小时内定个人出来,报给我,否则你们浙江出局了,长江以北我负责,长江以南秦永敏负责,以后的中国民主党没有你们浙江的份了。也许他怵于当时在吴义龙面前不加掩饰流露的对“位置”的极度渴望,他在电话中大骂吴义龙:“吴义龙这个小流氓想跟我玩,我玩死他!”我实在听不下去,就把话筒交给正好在身边的祝正明了。祝正明一声不吭的听着他骂,骂完了,挂了电话,祝正明对我说:“我们不理他,管自己。”

这个电话告诉各个朋友后,大家对北京的反应都很冷淡,王荣清觉得浙江应该选出一个负责人来,我知道这件事后,就对毛庆祥说,这个负责人就让年轻人去当吧,让他们锻炼锻炼,我们民主墙时期的年长者退下来为民主党的发展把把关,王荣清和李锡安对我的提议也没有反对意见。当时除了我们四个年纪大些的,年轻人只有祝正明和吴义龙了。祝正明反应平静,但是吴义龙却来劲了,要争做老大。王荣清就提出,六个人投票决定。投票结果四比二,祝正明四票,吴义龙二票。吴争不成就自荐他做对外发言人,大家都同意了。王荣清提出要我做秘书,因为我的威信放在那里,笔头还可以。我推辞,但是大家都附议,我只得接受下来,没想到王荣清又提出这个秘书要带个长,也被大家附议。

吴义龙满口含混不清的桐城官话在接受采访的时候让海外记者听不清,所以他们还是打电话来找我们几个老民运了解情况,吴义龙知道后,特意告诫大家:“你们以后不要再接受记者采访了,我才是发言人。”

-rId3-960X1280.jpeg)

1998年十二月初,接待来杭州声援王有才的各地朋友。

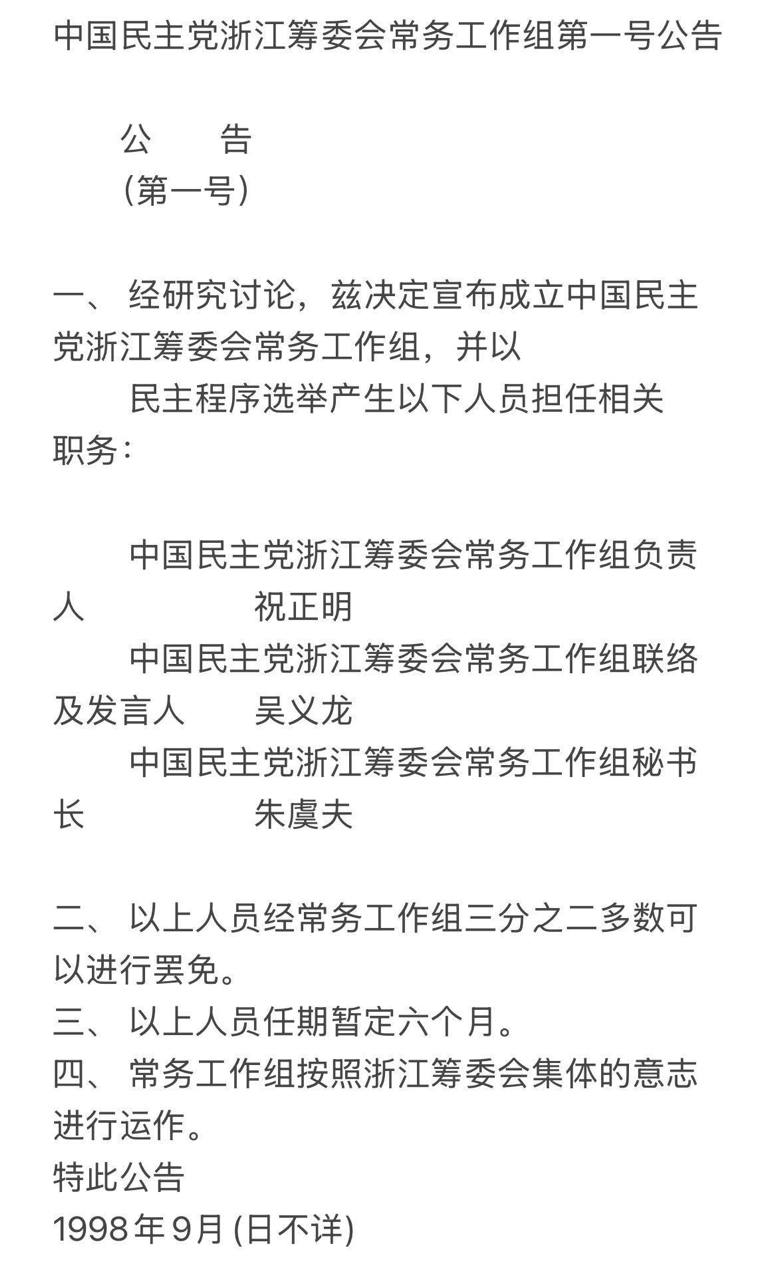

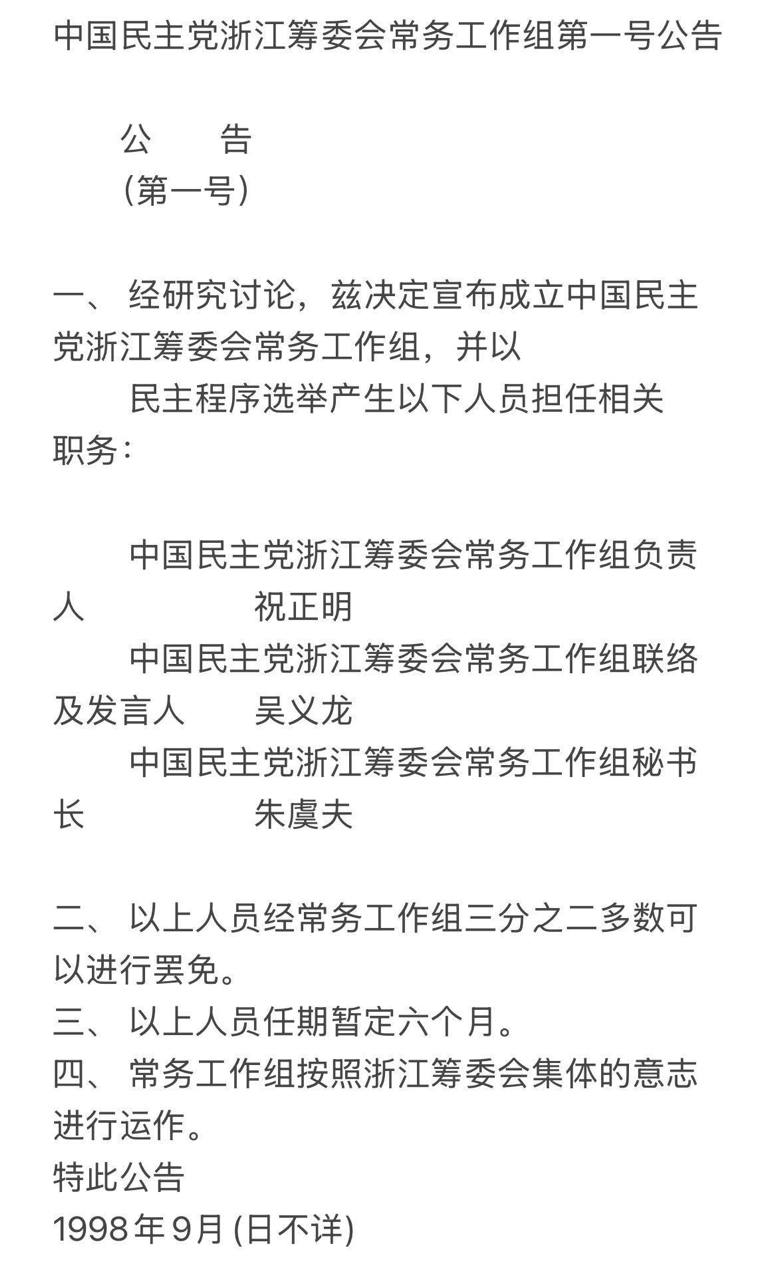

中国民主党浙江筹委会第一号公告

The Origins of the Democratic Party (Part V): From the Wildfires of Zhejiang to a Nationwide Blaze

By Zhu Yufu | Edited by Hu Lili | Chief Editor: Luo Zhifei | Translated by Lu Huiwen

With the arrival of summer, the flame of the pro-democracy movement in Hangzhou grew ever hotter. As Wang Youcai was repeatedly arrested and released, many visitors sought out the homes of us veteran activists. One particularly vivid memory I have is of Yin Weihong, drenched in sweat as she pedaled her rattling old bicycle under the scorching sun. Wang Peijian frequently dropped by to discuss legal issues related to founding a political party. Xu Guang, along with his wife Huang Xiaohang, brought their newborn baby to my house, along with his article “The Endless Arrests of Democratic Party Members.” I greatly admired the couple’s courage for venturing out with such a young child. Yan Zhengxue, an artist from Beijing, also braved the summer heat to find me in Hangzhou. I took him to Wang Rongqing’s house, but Yan later told me that Wang had sold him out to the police. Around the same time, Liu Xianbin and a journalist friend also visited from Sichuan. As I was not familiar with them, I kept mostly quiet. The reporter thus thought I was reserved, while the outspoken Zhu Zhengming was noted for saying things he later regretted, causing him some frustration.

-rId2-1280X960.jpeg)

After word of the Democratic Party’s founding spread in June 1998, many activists from across the country came to Hangzhou to “learn from our experience.” They hoped we could “spread the gospel” and energize the movement across provinces. Whenever we gathered, we discussed sending people out to “ignite the flames” in other regions. Wu Yilong volunteered, as everyone else had jobs or businesses. He had just submitted his master’s thesis and was free. Everyone agreed.

We pooled money for his travel expenses and compiled a list of key contacts in each province. At the time, the pro-democracy movement was largely based on signing petitions in response to major events, so many of us had each other’s contact information. We listed the active individuals on a single sheet, and Wu was to “follow the map” as he visited each location. Wang Rongqing covered most of the travel expenses, while others contributed what they could. Yao Zunxian, who had been actively involved in Hangzhou, agreed to accompany Wu (we later learned that Yao covered all food and lodging costs). Yang Hai would still recall decades later that Wu flew to Xi’an—but Wu never mentioned this to us.

Activists from Sichuan (Liu Xianbin), Hunan (Xie Changfa), Xi’an (Fu Sheng), Liaoning (Tang Yuanjun and Leng Wanbao), Chongqing, Heilongjiang, Gansu, Yunnan, and Guangdong all came in turn. In late July 1998, Qin Yongmin from Wuhan—an old friend of Mao Qingxiang—was visited by Mao. When Mao returned, he told me it had been swelteringly hot in Wuhan. They found Qin asleep at his small market stall selling gas stoves and pressure cooker parts. A fax machine sat on the table—Qin was running Human Rights Watch at the time. They woke him up and invited him to help form the Democratic Party. Qin readily agreed and immediately began organizing the China Democracy Party Hubei Preparatory Committee.

The name “China Democracy Party Zhejiang Preparatory Committee” was chosen deliberately. At the time, Wang Youcai was open-minded and disdained personal power. He created a platform where each province could have its own stage. However, Wang disapproved of my street-level political activism and my habit of recruiting “riff-raff” into the party. He believed there should be a “threshold” for joining, just like there is in regular employment. The most criticized decision I made was bringing Wang Rongqing into the party, as many believed he had once collaborated with the police during the Democracy Wall movement. I was helpless in this regard—our fledgling party had so much to do but lacked people to do it. We had to make use of everyone, even the rogues and thieves. Zhejiang’s self-identification as only the “Zhejiang Preparatory Committee of the China Democracy Party”, rather than claiming national leadership, left room for others to build their own committees. This humility encouraged the growth of the movement and set a positive example.

Later, I learned from Wang Xizhe that overseas support groups were doing everything they could to assist the organizing efforts in China. They helped buy fax machines and solve other practical problems.

Wu Yilong encountered an awkward situation in late August 1998. He visited a prominent figure in Beijing and asked him to help form the party there. The man cautiously invited Wu inside and asked, “If I were to do this, what position would I get?” Wu was stunned—he was there to “ignite a flame,” not hand out leadership roles. The atmosphere turned awkward. Seeing Wu hesitate, the man dismissed him: “Leave—I won’t do it.”

It was scorching hot, and Wu, drenched in sweat, asked to take a shower before leaving. The man led him to the bathroom, but Wu took so long that the host grew suspicious and checked in. Finding Wu’s tattered underwear hanging on the door—full of holes like a fishing net—he tossed them out and left a new pair. When Wu couldn’t find his underwear afterward, he shouted. The host told him to wear the new pair. Later, because Wu shared this story, the man felt humiliated and publicly mocked Wu: “That little punk tried to play games with me—I left him without underwear!” A bit of comic relief in hard times.

Afterward, Wu visited Ren Wanding, who agreed without hesitation to form the China Democracy Party Beijing Preparatory Committee, and on September 17 submitted an application to the Beijing civil affairs department.

Meanwhile, the same man who had refused to support the party earlier launched his own initiative: a “Read More, Make More Friends, Delay Forming Associations” campaign, but it gained little traction. As party committees sprang up across China, he couldn’t sit still. On November 6, he suddenly announced the First National Congress of the China Democracy Party. This was met with strong opposition, especially from Zhejiang, as he was now trying to hijack the movement after previously opposing it.

By November 9, he had set up a “China Democracy Party Beijing-Tianjin Party Branch,” appointing himself chairman, and filling six of seven key posts. Lu Honglai of Tianjin was named a vice chairman—though he happened to be in Hangzhou selling fruit and hadn’t been consulted. I asked him, “What’s this vice chairman thing?” Lu replied, “That guy is just like that. Didn’t even ask me before putting my name down.”

That man had been the first to oppose forming the Democratic Party, and all of this was publicly documented at the time. After failing to stop the movement, he gathered a few people and set up his own “China Democracy Party.” Although he managed to create a “Beijing-Tianjin branch,” the regional committees largely ignored him. He then tried a new tactic: convincing Qin Yongmin that the preparatory committees were progressing too slowly, and that a national leadership body was urgently needed.

Soon after, he established the China Democracy Party National United Headquarters in Beijing. Seeing Zhejiang as a thorn in his side, he called me to say he was forming a national party leadership with himself as chairman. He planned to appoint two vice chairmen—one being Qin Yongmin—and told us Zhejiang must appoint someone within 24 hours or be excluded. “I’ll handle everything north of the Yangtze; Qin Yongmin will manage the south. If you don’t cooperate, Zhejiang will be left out of the China Democracy Party,” he warned.

Perhaps remembering how openly he had lusted for a leadership position in front of Wu Yilong, he now berated him on the phone: “That punk tried to play with me? I’ll ruin him!” I couldn’t stand to listen anymore and handed the phone to Zhu Zhengming, who silently listened until the call ended. Then he told me, “We’ll ignore him. Let’s just do our own thing.”

After informing the others about the call, everyone responded coolly. Wang Rongqing suggested Zhejiang select a representative. I spoke to Mao Qingxiang, proposing that we older activists from the Democracy Wall era step back and let the younger generation lead. Wang and Li Xian agreed. At the time, the only younger members were Zhu Zhengming and Wu Yilong.

Zhu remained calm, but Wu became eager to be the leader. Wang suggested a vote among six members. The result: four votes for Zhu, two for Wu. Failing to win leadership, Wu nominated himself as spokesperson, and everyone agreed. Wang then suggested I be the secretary because of my reputation and writing skills. Though I declined, everyone insisted, and I accepted. Then Wang added that the secretary should also be “chief secretary”—a motion that also passed.

Due to his thick Tongcheng accent, foreign journalists struggled to understand Wu during interviews, so they still contacted us veterans. When Wu found out, he warned us: “You must stop talking to reporters. I’m the only spokesperson now.”

-rId3-960X1280.jpeg)

China Democracy Party Zhejiang Preparatory Committee — Announcement No. 1