作者:何愚

编辑:钟然 责任编辑:罗志飞 校对: 李杰 翻译:彭小梅

这是我在疫情期间拍到的一些在电梯里的照片。

他们的脸有的被挖了眼睛,有的被扣了嘴巴,有的被涂鸦。这样的照片我有几十张,我每到一个陌生的电梯里,我就会看到这样的景象,于是我就用手机拍了下来。

疫情最严的那段时间,我被封在家里,哪儿也去不了。小区的大门被封条封死,铁栅栏拦得密不透风。快递进不来,物资靠抢,核酸排长队,有时候咽口水都像犯法。那段日子,手机成了我唯一的信息来源,电梯成了我和世界唯一的接触点。

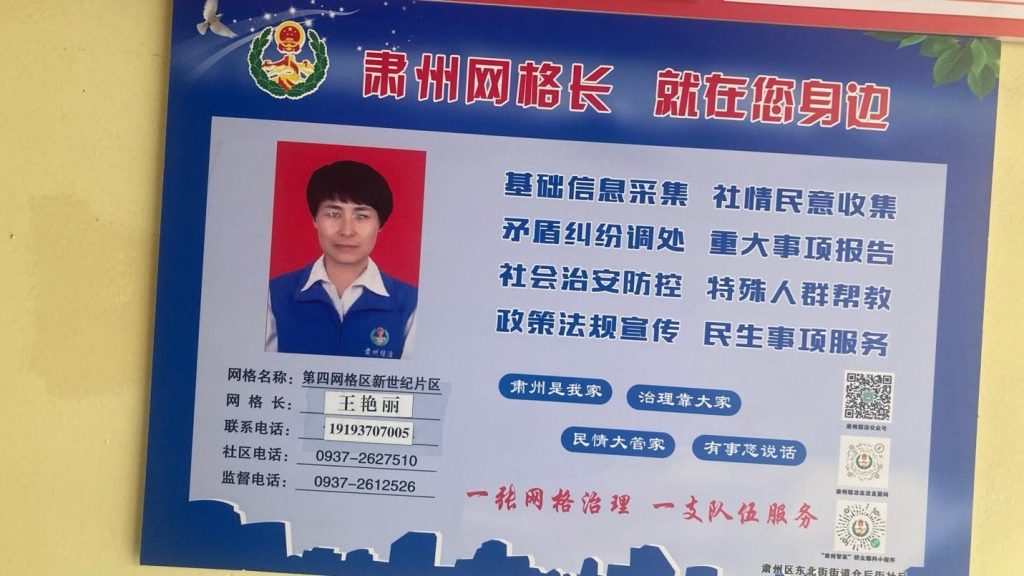

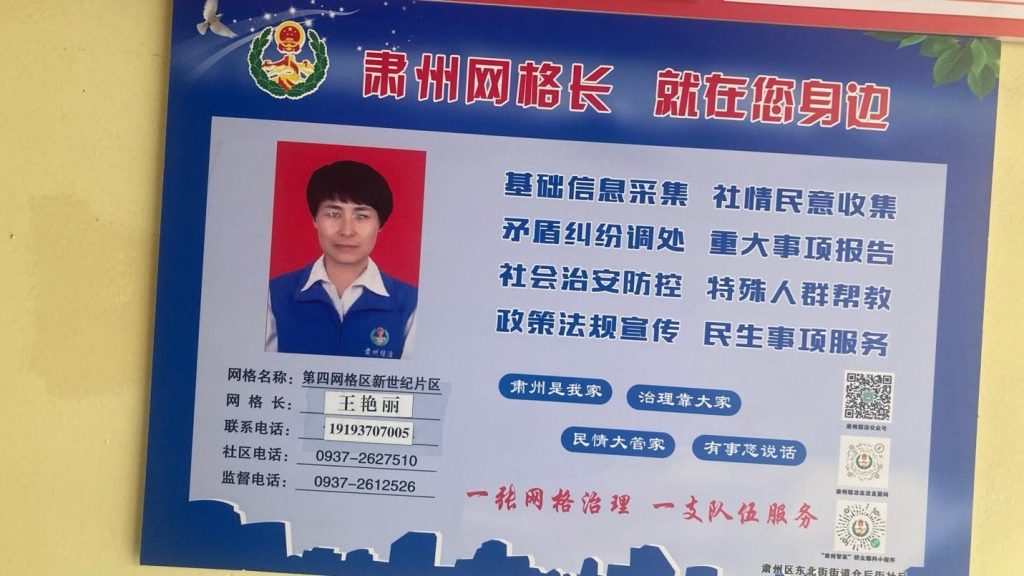

就是在那个狭小的电梯里,我一次次看见那些“网格长”的照片。

每一张都差不多:红底证件照,身穿蓝马甲,名字、手机号、社区电话、监督电话,一应俱全。贴得规规整整,看上去像是“服务群众”的标牌。

但几天后我发现,那些照片开始“变形”。

第一张脸被人用钥匙划破了,从额头一直到下巴,像一道刀口。过两天,有的照片被烟头烫得焦黑,鼻子和嘴巴几乎被烧没。有的被泼了墨水,有的贴上黄色符咒,还有的整张脸被涂得乱七八糟,只留下白色眼白在黑油里发亮。

我知道,这不是无聊的人在破毁。这是歇斯底里的反抗,这是民众对政府唯一敢做的行为。是中国古代的厭胜之术。是一种极度压抑下的反抗。

不是反抗“党兴军”这个人,而是反抗她代表的那套系统——

她只是被选来贴在电梯里的脸,但背后是封控命令,是24小时看守,是“有困难找网格长”的口号和“你不配知道政策”的冷漠,是你家门被焊死时她不接电话,是你阳性了没人管、她却催你签字“自愿隔离”的那份纸。

他们说:“网格长是为大家服务的。”

可在疫情里,他们变成了国家意志的代言人,变成了小区里最大的权力节点。他们可以决定谁能出门,谁不能;谁能领菜,谁被落下;谁家的门被钉死,谁家能留条缝通风。

没有申诉渠道,没有新闻记者,也没有法律支持。那些被误封、被殴打、被饿得崩溃的人,求助无门。

所以人们开始对电梯墙上的那张脸下手——不是因为他们疯了,而是因为他们终于明白:没有人会替你说话,也没有人会替你出头。你唯一能做的,是毁掉那张代表权力的脸。

在一个正常的社会,这应该是最后的选择。但在中国,这是人们唯一的选择。

疫情之后,我重新回看这些照片,有种深深的恐惧。

中国不是没有反抗,只是没有被允许存在的反抗。不是没有愤怒,只是这些愤怒被逼到最隐蔽的角落。一个国家,连“骂一句”都变成风险,百姓只能靠“划脸”来发泄,这样的治理,不是文明,是极权的深水区。

“网格化治理”使中国真正变成一个世界超级大监狱。从新疆的“再教育营”,到西藏的“维稳尖兵”,再到疫情期间全国范围内的居家封控,国家机器把每个人都装进了格子里,大格子套小格子,层层管理。每层大门都有一个钥匙的掌管者。

而网格长,就是这些格子的最小单元。

没有铁门、没有高墙,但每一个人都知道自己被盯着、被记着、被系统标注着。

这些照片深深地触动了我。不是因为它们多残酷,而是因为它们太真实。它们不是拍出来的新闻,而是压抑出来的证据。

它们证明,普通人不是没有感受,不是不明事理。他们只是没地方说,只能在最微小的空间里,对抗一整套国家系统(用全世界六分之一人口的血打造的政府系统)。

我们终究不是木头。我们也想活得像人。但在这个体制下,连这一点点尊严,都变成奢望。

在中国,有一群人,他们曾经悄悄地,在电梯里,诅咒过那个逼他们沉默的人。

他们不是疯子。他们只是活不下去了。

Chinese Resistance

Author: HE Yu

Editor: ZHONG Ran · Executive Editor: LUO Zhifei · Proofreader: LI Jie · Translator: PENG Xiaomei

Those are the photos taken inside elevators during the pandemic.

In each confined elevators, the same images kept appearing: faces of “grid officers” staring from laminated posters. Some had their eyes gouged out. Others had their mouths scratched off, their faces blackened by spray paint or cigarette burns. I took dozens of such photos across cities and it happened almost in every elevator I went.

During the strictest lockdown, I was locked inside my apartment. The gate was welded shut, fences wrapped the compound like a cage. No couriers, no groceries, no escape. Lines for testing stretched endlessly; even swallowing felt like breaking a rule. My phone became my only link to the world, and the elevator—my only public space.

Inside that elevator, I met the same red-background ID photo again and again: a person in a blue vest, their name and phone number printed beneath the title Grid Officer. The poster looked neat, almost bureaucratically kind—“Serving the People,” it claimed.

But days later, the images began to “warp”.

One face was slashed from forehead to chin, as if by a knife. Another was charred, its mouth erased by flame. Some were splattered with ink, some plastered with yellow talismans. A few were smeared entirely black, except for the white of the eyes glowing through.

This was not vandalism. It was revolt. A silent, desperate curse against the faceless machine of control.

I know this isn’t bored people messing things up. This is a hysterical act of resistance—the only thing ordinary citizens dare do against the government. It is China’s ancient “yansheng” practice—an apotropaic curse—a form of defiance born of extreme repression.

It is not a revolt against the individual “Dang Xingjun,” but against the system she represents—

She’s just the face chosen to be pasted inside the elevator. Behind it are lockdown orders, 24-hour surveillance, the slogan “If you have difficulties, call your grid chief,” and the cold reply “You don’t deserve to know the policy.” It’s her not answering the phone when your door is welded shut; it’s no one caring when you test positive—yet she’s the one pressing you to sign that paper saying you “voluntarily” agree to quarantine.

They said: “Grid officer serve the community.”

But during the lockdowns, they became extensions of the state—miniature governors of each building. They decided who could leave, who could eat, whose door stayed welded shut.

There were no appeals, no journalists, no law. Those wrongly locked in or starved into madness had no recourse but silence.

So people began to go after that face on the elevator wall—not because they’d gone mad, but because they finally understood: no one will speak for you, and no one will stand up for you. The only thing you can do is destroy the face that represents power.

In a normal country, this would be the last act of desperation. In China, it was the only possible act of resistance.

After the pandemic, I looked again at those photos—and felt a deep chill.

It’s not that Chinese people never resist; it’s that resistance is never allowed to exist. It’s not that anger is absent; it’s that anger has been forced underground, into gestures as small as scratching out a face. A country where cursing aloud is dangerous, and where people can only rebel with a key and a poster—that is not civilization, but totalitarianism in its purest form.

“Grid governance” has turned China into a giant, invisible prison. From the reeducation camps of Xinjiang to the “stability squads” in Tibet, to the welded doors of locked-down cities, the state has placed every citizen into a lattice of control—big grids, small grids, every door under a keyholder’s command.

The grid manager is the smallest cog in that machine, the micro-level warden of the super-prison.

No visible bars, no walls—but everyone knows they are watched, logged, and tagged.

These photos are not tragic because they are violent. They are tragic because they are true.They are not journalism. They are evidence—evidence of what people feel when every word is censored and every scream must be silent.

Ordinary people are not fools. They understand everything. They simply have no space left to speak. So they resist in the smallest space possible—an elevator, a poster, a face.

We are not wood. We are human beings. We want to live with dignity. But under this system, even dignity is a privilege beyond reach.

There was a time, not long ago, when countless people across China silently cursed the face that enforced their silence.

They were not mad. They were simply human beings trying, somehow, to breathe.

血祸 钟然 刘芳翻译-rId8-362X242.jpeg?w=218&resize=218,150&ssl=1)

毒雨下的花朵-rId6-881X662.jpeg?w=218&resize=218,150&ssl=1)

方舱纪实-rId4-600X400.jpeg?w=218&resize=218,150&ssl=1)

血祸 钟然 刘芳翻译-rId8-362X242.jpeg?w=100&resize=100,70&ssl=1)