民营资本为何屡遭打压

作者:景辉辰 2025年08月16日

编辑:周志刚 责任编辑:罗志飞 翻译:程铭

作为一名亲历中国现实的公民,我深切感受到中国的体制并不是它所宣称的“社会主义”,而是一种赤裸裸的党国资本主义与极权统治结合的模式。在这种体制下,中共既是裁判,又是选手,既掌控国家机器,又操控经济命脉。任何独立的力量,特别是民营资本,都会被视为威胁并遭到打压。

近年来,我亲眼看到中国的民营资本接连遭遇重击:互联网巨头被罚,地产大佬轰然倒下,许多企业家被迫沉默甚至逃离海外。这不是个别政策的偶然,而是中共统治逻辑的必然结果。

2021年4月,市场监管总局以“二选一”等垄断行为为由,对阿里巴巴集团处以182.28亿元人民币罚款(相当于其2019年中国境内销售额的4%)恒大陷入债务泥潭、违约暴雷。

从2021年“三道红线”政策开始,多个开发商出现资金链断裂,恒大项目停工、债务违约,并于2024年被香港法院下令清算。此背景下,“地产大佬”真实意涵即指如恒大等依赖高杠杆发展的房企的迅速倒下。

曾主导华晨帝国的企业家仰融因失去政治依靠而被撤职,后被控“国有资产流失”,最终逃往美国定居,事业一落千丈。

在党国资本主义下,国企寡头化成为常态。能源、金融、土地等关键资源全部掌握在中共手中。总书记如同“董事长”,中共是最大的股东,国家机器和国企既是经济工具,也是政治工具。这样的体制,实际上就是通过权力来垄断资本,并压制一切社会独立性。

民营资本的困境格外突出。许多民营企业家原本寄望于改革开放,却发现自己随时可能被整肃。“反垄断”“去杠杆”“共同富裕”这些口号,其实是打压民营资本的借口。民企一旦做大,就会被视为威胁;失去政治庇护,即便是庞大的商业帝国,也可能顷刻倒塌。

我身边的朋友也有企业在打压中被迫关停,他们的人生和事业瞬间崩塌,这让我第一次真切地体会到:在中共的体制下,任何独立资本都可能随时被摧毁。更严重的是,我自己的企业也遭遇了同样的命运——不仅持续受到打压,还被当局设下陷阱,最终甚至被强行没收。这一切彻底击碎了我对所谓改革开放的幻想,也让我明白:在中共的极权统治下,企业和个人的努力都无法换来安全,随时可能被剥夺一切。

这种体制的后果已经显现:

创新活力被扼杀,市场信心崩溃;

社会阶层固化,贫富差距进一步扩大;

普通民众生活在恐惧中,既害怕失去自由,也担心经济未来。

中共用这种方式维系统治,不仅剥夺了社会活力,也彻底扼杀了民众对公平与希望的追求。民营资本的被打压,不仅是经济问题,更是专制机器压制自由的延伸。

民营资本屡遭打压,表面上是经济问题,本质却是党国资本主义与极权逻辑使然。只要这种体制不改变,中国社会的创新活力、民众的自由与安全都无法得到保障。

今天,我能在海外自由写下这些文字,但我十分清楚,如果在中国发出同样的声音,这样的呼吁只会招致打压与惩罚,而不是宽容与对话。

正因为如此,我必须坚定地表达立场:反对中共暴政,反对党国资本主义对民营资本和普通民众的压迫。我相信,只有当权力与资本真正分离,国家不再既当裁判又当选手的时候,中国社会才可能走向公平、自由与安全。

Why has private capital been repeatedly suppressed?

–The truth of party-state capitalism

Author: Jing Huichen August 16, 2025

Editor: Zhou Zhigang Responsible Editor: Luo Zhifei Translator: Ming Cheng

Abstract: The article reveals the principle of economic operation under the Communist Party of China system. How did China’s state-owned enterprises begin to support private enterprises, then steal the economic achievements of private enterprises, then squeeze private enterprises, and then monopolize the resources of all levels of the country? The ultimate purpose of the Communist Party of China is to steal interests by deceiving the Chinese people and the international community.

As a citizen who has experienced the reality of China, I deeply feel that China’s system is not the “socialism” it claims, but a naked model of combining party-state capitalism and totalitarian rule. Under this system, the Communist Party of China is both a referee and a player, not only controlling the state apparatus, but also controlling the economic lifeline. Any independent force, especially private capital, will be regarded as a threat and suppressed.

In recent years, I have seen with my own eyes that China’s private capital has suffered a heavy blow one after another: Internet giants have been punished, real estate tycoons have fallen, and many entrepreneurs have been forced to remain silent and even flee overseas. This is not the accident of individual policies, but the inevitable result of the logic of the Communist Party’s rule.

In April 2021, the State Administration of Market Supervision imposed a fine of 18.228 billion yuan on Alibaba Group (equivalent to 4% of its domestic sales in China in 2019) on the grounds of “two-choice-one” and other monopoly behaviors. Evergrande fell into a debt quagmire and defaulted.

Since the “three red lines” policy in 2021, many developers have broken their capital chains, Evergrande projects have stopped work, defaulted on debt, and were ordered to be liquidated by the Hong Kong court in 2024. Against this background, the true meaning of “real estate tycoon” refers to the rapid collapse of real estate enterprises such as Evergrande, which rely on high-leverage development.

Yang Rong, an entrepreneur who once dominated the Brilliance Empire, was dismissed due to his loss of political reliance. Later, he was accused of “loss of state-owned assets” and finally fled to the United States to settle down, and his career fell dramatically.

Under the party-state capitalism, the oligarchy of state-owned enterprises has become the norm. Energy, finance, land and other key resources are all in the hands of the Communist Party of China. The general secretary is like the “chairman”, and the Communist Party of China is the largest shareholder. The state apparatus and state-owned enterprises are both economic and political tools. Such a system is actually to monopolize capital through power and suppress all social independence.

The plight of private capital is particularly prominent. Many private entrepreneurs originally expected reform and opening up, but found that they might be purged at any time. The slogans of anti-monopoly, “deleveraging” and “common prosperity” are actually excuses to suppress private capital. Once private enterprises become large, they will be regarded as a threat; without political shelter, even a huge commercial empire may collapse in an instant.

Some friends around me also have enterprises forced to shut down in the suppression, and their lives and careers collapsed in an instant. For the first time, I truly realized that under the system of the Communist Party of China, any independent capital may be destroyed at any time. More seriously, my own business suffered the same fate – not only was it continuously suppressed, but it was also trapped by the authorities, and even forcibly confiscated. All this completely shattered my illusion of the so-called reform and opening up, and also made me understand that under the totalitarian rule of the Communist Party of China, the efforts of enterprises and individuals cannot be exchanged for security, and may be deprived of everything at any time.

The consequences of this system have emerged:

– The vitality of innovation has been stifled, and market confidence has collapsed;

– The social class is solidified, and the gap between the rich and the poor is further widened;

– Ordinary people live in fear, fearing both of losing their freedom and worrying about the future of the economy.

This way of maintaining social governance in China not only deprives social vitality, but also completely stifles the people’s pursuit of fairness and hope. The suppression of private capital is not only an economic problem, but also an extension of authoritarian machinery suppressing freedom.

Private capital has been repeatedly suppressed. On the surface, it is an economic problem, but in essence, it is caused by party-state capitalism and totalitarian logic. As long as this system is not changed, the innovative vitality of Chinese society and the freedom and safety of the people cannot be guaranteed.

Today, I can write these words freely overseas, but I know very well that if the same voice is made in China, such an appeal will only attract suppression and punishment, not tolerance and dialogue.

For this reason, I must firmly express my position: oppose the tyranny of the Communist Party of China and the oppression of private capital and ordinary people by party-state capitalism. I believe that only when power and capital are truly separated

When the country is no longer both a referee and an elected hand, Chinese society can move towards fairness, freedom and security.

疫情三部曲(番外)— 蚊城记

作者:张致君

编辑:何清风 责任编辑:罗志飞 翻译:何兴强 校对:冯仍

“堵水以防蚊,正如捂耳以止鸣;于是耳朵静了,蚊却在心里飞。”

今年城里忽然多了个新名词,叫“基孔肯雅热”。名字绕口,像一条打结的绳。绳子一打结,许多脑袋便舒坦了:有了名词,就有对策;有了对策,就有公文;有了公文,就有成绩。成绩要上墙,上墙之前,先把城里的下水道一律装上纱网。纱网雪白,像给井口盖上了被子——盖得很孝顺。

纱网的用处,公文说得极详:可阻蚊、可断链、可护民。只是雨来了,雨不识字,冲到纱网上,犹豫了一下,便站成一汪汪积水。积水里蚊子生得更勤,像遇到了公费的产房。于是有人建议再加一层更密的网,以杜后患。网越密,水越闷;水越闷,蚊越壮。壮到黄昏时分,黑云一抖,城便响成一锅。

我在街角看见几个小吏捧着卷尺,蹲在井边丈量“网孔标准”。他们一丝不苟,像在选拔孔雀的羽。丈量完了,便抬头望天:今日任务饱满。饱满是个好词,像刚煮开的馒头;只是馒头若闷在笼里,久之也会落水。落水的馒头不易咽,但仍可统计为“发放完毕”。

对策不止一条。为了“源头斩断”,城里又想到了菜园。说菜园滋水,水滋虫,虫滋病。于是派人去封,水泥推成白浪,一浪浪扑到青菜上。青菜来不及喊,便直挺挺站成了纪念碑。纪念碑的题名叫“环境整治”。整治之后,蚊子仍在;只是菜不在了。没有菜,便少了积水;少了菜,也少了人心——人心向来怕见水泥。

有个老夫妇守了一角方寸的土,种的是葱与蒜。蒜不怕味重,葱不怕天冷。小吏来时,他们把锄头立在脚边,问:“这也封?”小吏笑,笑得像公事包的扣:“封一点,放心。”于是水泥从葱蒜根部缓缓爬上来,像一层殷勤的霜。老头沉默,老太太问:“那蚊子呢?”小吏更笑:“我们还要全民抽血呢!”老太太一怔,像被门把磕了额头。

抽血是更科学的法子。科学这两字一出,人人肃然。队伍像旧年核酸时那样排起来,袖子挽上去,血管一根一根报到。管子收满了,放在银亮的托盘里,像一排不容争辩的红逗号。逗号多了,句子就长;句子一长,意义便由上面解释。解释里自然免不了几个好听的词:监测、预警、筛查、呵护。呵护是好词,尤其对流动的血说起,显得极为体贴——仿佛血是国家的,共有的,暂住在你体内,随叫随到。

抽完血的手臂上贴一张小方片,像兵营里的号牌。有人问:“我并不病,为何抽?”答曰:“大局需要。”大局是个无形的胃,饿的时候,会把零碎的日子一并吞下。吞下之后,过几日又说饿;于是再抽。抽血的好处,在于看得见:袋里鲜红,统计报表也鲜红。至于井里积水、天上蚊云、菜地水泥,那些颜色不太入账。

我在报上见到一则图解,标题写:“从源头到末端,织密防蚊网。”图上箭头四方八面,像四个队长同时指挥操练。操练需要队列,队列需要口号,口号需要响亮。于是街道有了喇叭,喇叭里有了“请立即处理自家积水容器”的慈声;又有“如发现阳性滋生地,立即报告”的威声。慈威交替,像老旧钟楼撞了晴天。钟楼从不去井边看一眼,它只负责数点。

人间也有“看一眼”的人。他们蹲在井边,翻起纱网的角,想让水顺一顺。水顺了一小会,蚊也跟着顺。顺到一个拐角,又被另一层网截回。便像旧年防疫时,门洞贴着黄条,黄条贴得比风还疾:此巷通而不通,此路开而不开。老母去买药,绕了三道封条,回家药晾成了纪念品。那会儿城里学过一门绝技,叫“静默”。静默时,蚊子也静默;等一声令下,蚊子复活,人还要排队学习复活。

如今这门学问又翻出来。小吏戴着红袖标,会看网,会找水,会训话,也会合影。合影时,他们竖起大拇指,背景是刚封完的菜地。菜地不言,泥里渗出一点汁,像一张擦得太勤的脸。旁边贴了一张告示:“此处整改到位。感谢配合。”配合这词再度回归。它像一把万能扳手,套在谁身上都刚好。只是常被套的那批人,肩膀渐渐低了半寸。低半寸,才合群。

蚊子的学问,不在诗里,在水里。下水不畅,蚊便畅。纱网盖住了洞,没盖住逻辑。逻辑是个怪物,最恨“为你好”的好心。好心若走到极端,便成了一种熟悉的姿势:先堵,再看;先封,再讲;先采,再说。说来都为众生,做去却沿着表格。表格像方格纸,落在城上,把生人都画成了工整的字。字里有笔画,笔画里有小小的倒刺,扎在谁身上,谁就负责“理解”。

红卫兵式的小傻也不难见:冲锋,喊口号,抬着喷雾机,一路驱赶人影和良心。良心跑不过制度,回头一看,自己已戴上红袖标——原来良心也能被征用。征用之后,良心学会了审核:谁家的桶没倒,谁家的窗没关,谁家的狗碗积了水,谁家小孩笑得太响。笑得太响,容易招蚊;于是笑也得抽查。抽查久了,人便学会了“安静生活”,像旧年的“安静小区”:出门凭证,进门扫码,咳嗽报备,呼吸限频。

我在心里替这些词排了一个家谱:封控生封条,封条生关卡,关卡生告示,告示生口号,口号生合影,合影生总结,总结再生封控。至于蚊?蚊是旁系,见缝插针,逢雨成灾。灾与封控互相倚仗,彼此成全,像两条握在一起的手:一条冷,一条热,最终都伸向了你的手臂——抽血那一刻,针头入皮,谁也不问你愿不愿意,谁也不问井底的水愿不愿意。

有人说:这不过是一阵子;过阵子雨停,蚊散,网烂,泥干,一切复旧。复旧这词很安慰,像给病人说“明日就退烧”。只是城里有一种热,不是热度,是热心——热心铺出来的路,直通封控的旧仓库。仓库很大,里面堆着“三年所学”:封、卡、扫、查、报、贴、剪、封。每个字都练得极熟,像随时要上阵。上阵从来不缺号角,缺的是回头。回头一望,井盖下的水黑而静,静得像一个不肯再被打扰的夜;再望,水面之上,纱网正轻轻抖动,像一张没合上的嘴。

忽想起一位老友,旧年给我说:瘟疫教会人两件事,一是如何不去看,二是如何只看表面。表面是干净的证件,合格的栏杆,标准的网孔,热心的合影。至于井里翻腾的那点浑,最好不谈。谈多了,会被蚊叮:你传播负能量。负能量这四字像蚊香,绕你三匝,叫你昏睡。昏睡的人不会去翻网角,不会去拔水泥;昏睡的人最体面,适合合影。

雨点打在纱窗上,像数不清的小问号。我想去路口看看积水,撑伞下楼。楼下的井口戴着新网,网目细得像强迫症;旁边的菜畦是一整块新水泥,水泥上画了一个笑脸,似乎在安慰谁。我忽然起了一个坏心思,伸手把网角掀起一指;水在下面挪了挪腰,喘了一口气。那一口气里,似乎有去年冬天压下的叹息。我又把网放回原处,像把刀悄悄插回鞘。插得轻,才不会惊动什么“整治小组”。

回到屋里,我把这篇文字放在桌上,像一块没凝固的水泥。它若干了,会裂;裂纹里要长草。草长出来,蚊也会来。到那时,或许又有人提议:再加一层更密的网。网格如棋,棋子的去路便少了一半。至于城,照样会出通告、排队、抽血、合影;照样会把“为你好”印成红字,贴在每一道我们必须经过的墙上。墙越来越白,心越来越黑,蚊越来越肥,水越来越闷。只有雨,还是那样落下——落在网的正中,发出轻轻的一声:噗。

倘有人问:如何防蚊?

我答:先让水走路,再教网做人;若还不成,先学会把门从里头打开,而不是从外头封死。至于抽血,且把针拔慢一点,慢到能听见那一小点良心“咔嗒”入位的声。

The Pandemic Trilogy (Epilogue) — Chronicle of the Mosquito City

Abstract: This year, a new term suddenly appeared in the city—“chikungunya fever.” Yet the city knows of another kind of fever, not heat, but fervor—the fervor that paves a road straight into the old locked-up warehouse. The warehouse is vast, and inside are piled “three years of lessons”: How to prevent mosquitoes?

Author: Zhang Zhijun

Editor: He Qingfeng

Chief Editor: Luo Zhifei

Translation: He Xingqiang

“Blocking water to prevent mosquitoes is like covering one’s ears to stop a ringing sound; the ears may fall silent, but the mosquitoes still buzz inside the heart.”

This year, a new term suddenly appeared in the city: chikungunya fever. The name is knotty, like a twisted rope. Once the rope is tied, many minds feel at ease: with a new term comes a countermeasure; with a countermeasure comes an official document; with a document comes an achievement. Achievements must be displayed on walls, but before that, all the city’s drains are covered with mesh screens. The mesh is snowy white, like a quilt tucked over the mouths of wells—so pious, so “filial.”

The utility of the mesh is written in detail in the official documents: it blocks mosquitoes, severs transmission, protects the people. But rain does not read. When it pours down onto the mesh, it hesitates for a moment, then gathers into stagnant pools. In the stagnant water, mosquitoes breed with renewed vigor, as if they had stumbled into a government-funded maternity ward. Someone then proposes adding another, denser layer of mesh to prevent further harm. The denser the mesh, the more suffocated the water; the more suffocated the water, the stronger the mosquitoes. By dusk, when dark clouds shudder, the city rings like a cauldron at full boil.

At a street corner, I saw a few minor clerks holding measuring tapes, squatting by the drains, meticulously gauging “mesh standards.” They worked as carefully as if selecting peacock feathers. Once measured, they looked up at the sky, content: today’s task fulfilled. Fulfilled is a fine word, like a freshly steamed bun; but if left too long in the steamer, the bun becomes soggy. Soggy buns don’t swallow easily, yet still count toward “distribution completed.”

Countermeasures never stop at one. In the name of “cutting off at the source,” the city turned its attention to vegetable gardens. They said gardens breed water, water breeds insects, insects breed disease. And so people were dispatched to seal them off—cement poured in waves of white, crashing upon the greens. The vegetables had no time to cry out before standing stiff as monuments. The title carved upon the monument: Environmental Rectification. After rectification, mosquitoes remained; only the vegetables were gone. Without vegetables, there was less standing water; without vegetables, there were also fewer hearts at peace—for human hearts fear cement more than pests.

An old couple guarded a small patch of earth, planted with scallions and garlic. Garlic fears no strong odor; scallions no cold. When the clerks arrived, the couple stood with their hoes at their feet and asked, “Seal this too?” The clerks smiled—the smile of a briefcase clasp: “Just a little. Don’t worry.” So the cement crept slowly up the roots of the scallions and garlic, like an eager frost. The old man stayed silent; the old woman asked, “And the mosquitoes?” The clerks smiled wider: “We’ll be drawing blood from everyone soon!” The old woman froze, as if her forehead had struck a doorknob.

Blood draws are a more scientific method. Once the word science is uttered, everyone stands solemn. The queues stretched long, just as in the days of mass PCR testing—sleeves rolled up, veins reporting one by one. Tubes filled with blood lined the silver trays, like rows of indisputable red commas. Commas multiplied, sentences lengthened, and meanings were then explained from above. The explanations never failed to include pleasant words: monitoring, early warning, screening, protection. Protection is a beautiful word, especially when spoken of flowing blood—it makes the blood seem national, communal, merely lodging in your body temporarily, ready to answer the call.

On each arm, after the draw, a square sticker was affixed, like an army tag. Someone asked: “But I am not sick—why draw my blood?” The answer: “For the greater good.” The greater good is an invisible stomach; when hungry, it swallows even the smallest scraps of daily life. After a few days, it hungers again—so more blood must be drawn. The benefit of blood draws is visible: the bags are red, and the reports are red. As for the stagnant drains, the mosquito swarms, the cemented gardens—those hues rarely enter the record.

In the newspaper, I saw an infographic titled: From Source to Endpoint, Weave a Dense Mosquito Net. Arrows shot in all directions, like four commanders drilling troops at once. Drills require formations, formations require slogans, slogans require volume. And so loudspeakers echoed in the streets: “Please promptly dispose of standing water containers at home” spoke the gentle voice; “Report any positive breeding grounds immediately” barked the stern one. Kindness and severity alternated, like an old clocktower tolling in bright weather. The clocktower never once looked down a drain; its sole duty was to count.

Yet there are still people who do look. They squat by the drains, lifting the corners of the mesh to let the water slip through. For a brief moment the water flows, and the mosquitoes along with it—until another mesh blocks the way. Just like the previous epidemic years, when yellow seals plastered doorways faster than the wind: streets open yet not open, paths free yet not free. An old mother fetching medicine circled three checkpoints, only to bring home pills turned into relics. Back then, the city had learned a strange art called “silence.” In silence, mosquitoes too were silent; until a command revived them, and people lined up once more to rehearse revival.

Now that art has returned. Clerks, red armbands bright, know how to inspect nets, identify water, lecture, and pose for group photos. In photos, they raise thumbs against the backdrop of freshly sealed vegetable plots. The plots say nothing, but from the soil seeps a thin juice, like a face rubbed too hard. Beside it hangs a notice: Rectification Completed. Thank You for Your Cooperation. Cooperation—that word returns again. It is a universal wrench, fitting snugly on anyone. Yet for those constantly tightened, their shoulders sink, half an inch lower. Lower, to blend in.

The study of mosquitoes lies not in poems, but in water. Where water stagnates, mosquitoes thrive. The mesh covers holes, but not logic. Logic is a beast, most resentful of “kindness for your own good.” Pushed to the extreme, such kindness takes on a familiar stance: seal first, see later; block first, explain later; take first, justify later. Always for the people, yet always along the form. Forms are graph paper laid over the city, reducing living beings to tidy characters. Within each stroke are tiny barbs, pricking whoever must “understand.”

The city is never short of little Red Guard types: charging forward, shouting slogans, wielding fog machines, chasing away shadows and conscience alike. Conscience cannot outrun the system. Turning back, it finds itself wearing a red armband too—so conscience, too, is conscripted. Once conscripted, conscience learns to inspect: whose bucket wasn’t emptied, whose window wasn’t shut, whose dog bowl had water, whose child laughed too loud. Laughter too loud attracts mosquitoes; therefore laughter, too, must be checked. Inspections prolonged teach people how to live “quiet lives,” like the “quiet communities” of old: entry by pass, exit by scan, coughs reported, breathing regulated.

In my mind, I draft a genealogy of these terms: lockdown begets seals, seals beget checkpoints, checkpoints beget notices, notices beget slogans, slogans beget photos, photos beget reports, reports beget lockdowns again. And the mosquitoes? They run collateral, slipping through cracks, thriving after rains. Disaster and lockdown rely on each other, complete each other, like two clasped hands: one cold, one hot, both reaching eventually for your arm. At the moment the needle pierces skin, no one asks if you consent; no one asks if the water in the drains consents.

Some say: it is only for a while. When the rains stop, the mosquitoes scatter, the nets rot, the cement dries, all will return to normal. Normal—such a soothing word, like telling a fevered patient, “Tomorrow the fever will break.” Yet the city harbors another fever—not temperature, but fervor—the fervor that paves a road straight into the old warehouse of lockdown. The warehouse is vast, crammed with “three years of lessons”: sealing, checking, scanning, reporting, pasting, cutting, sealing again. Each word drilled into muscle memory, ready for the front lines. Battle is never short of trumpets; only of a backward glance. Glance back, and the water beneath the manhole is black and still, like a night refusing interruption; look again, and the mesh trembles gently, like a mouth left half-open.

I recall an old friend, who once told me: Plagues teach two lessons—first, how not to look; second, how to look only at the surface. The surface is clean permits, qualified railings, standard mesh, enthusiastic group photos. As for the murky churn beneath the drain, best not spoken of. Speak too much, and the mosquitoes bite: You are spreading negativity. Negativity is like mosquito incense, circling you thrice, lulling you to sleep. The sleeping do not lift mesh corners, nor pry up cement; the sleeping are the most presentable—for photos.

Raindrops patter on the mesh window, like uncountable little question marks. I wish to see the standing water at the corner, so I take my umbrella downstairs. The drains below wear fresh nets, mesh so fine it looks compulsive. Beside them, the garden patch is a slab of new cement, with a smiley face drawn on top, as if to console someone. A mischievous thought comes to me: I slip a finger beneath the net and lift. The water shifts its waist, sighs once. In that sigh lingers the stifled breath of last winter. I lower the net back gently, like sliding a blade back into its sheath. Softly, so as not to startle any “rectification team.”

Back upstairs, I set these words on the desk, like a block of unset cement. Once hardened, it will crack; in the cracks, grass will grow. Where grass grows, mosquitoes will come. And then, someone will surely propose: another, denser net. Nets like chessboards, and half the moves erased. The city, unchanged, will still post notices, demand queues, draw blood, pose for photos. Still stamp for your good in red, pasting it upon every wall we must pass. Walls ever whiter, hearts ever darker, mosquitoes ever fatter, water ever more stagnant. Only the rain remains the same—falling, striking the mesh with a soft sound: puff.

And if someone asks: How should we prevent mosquitoes?

I answer: First, let the water find its way; then, teach the net to be human. If that still fails, learn to open the door from the inside, not seal it from the outside. As for drawing blood, withdraw the needle more slowly—slow enough to hear that faint click of conscience falling back into place.

疫情三部曲(三)— 影片余温

作者:张致君

编辑:何清风 责任编辑:罗志飞 翻译:何兴强 校对:冯仍

“世上有两样东西最怕热:一个是谎话,一个是镜头;偏生手心一热,它们就开始滴水。“

镜头是冷的。厂里出来时,它的心不过一块玻璃加几片金属;拿在手里,贴上皮肤,才慢慢升温。温度从哪里来?从掌心,从呼吸,从不合时宜的好奇。有人不喜欢这种温度,觉得发热的镜头像发炎的眼睛,会把不该长出来的东西拍出来。于是他们主张给镜头降温:罩袋、封存、断电、停用。冷到一定程度,镜头就学会“自我毁灭”:只拍风景,只拍花,只拍庆典的笑。

2022年冬天,有一只镜头拒绝降温。它被人举在街头,举得比白纸还高。镜头里,风从东到西,人从南到北,灯从亮到更亮。镜头没有说话,声音从四面八方撞进来,再从它背面无声地散开。它不过是个孔,却比许多嘴都会记事。

拿着镜头的人,我见过。他走路不快,像怕踩痛街上的影子。别人举口号,他举光圈;别人念标语,他念快门。他的肩不宽,肩上的带子却很稳,一头连着镜头,一头连着他不太出名的名字。名字后来出名了,是因为镜头有了温度——温度惹事。

我常思考,镜头为什么“惹事”?因为镜头记得太多。它记得人群里那只抖了一下的手,记得纸边的一滴雨,记得警觉从一双眼睛里迅速逃走,又从另一双眼睛里迅速回来。镜头是个忠诚的叙述者,忠诚到不肯删掉“无关紧要”的抖动与迟疑。不删的人,往往要被删掉。于是,镜头被套上袋子,名字被按在桌上。按住者微笑道:都是程序,别急。

程序是温柔的,它让冷变得理直气壮。冷的好处很多:器材不坏,记录不乱,解释不累。只是街头因此降到零度,零度之下,许多呼吸不见雾了,看起来像没有。没有呼吸的城市,睡得很沉——沉得像石头扔进湖底,不起泡,连鱼也不惊。

有人说:“镜头没有立场,它只是光学。”这话对,也不对。镜头确实只会进光,却会把光引向某个人的脸。那一刻,立场就长出来了,无需表态。镜头对准哭,哭就有位置;镜头对准笑,笑就有分寸。更多时候,镜头对准等待——排队、核酸、出示、扫码。等待久了,人会忘记自己在等什么,于是镜头替他记。最可怕的不是镜头看见了你,是你习惯镜头看见你;更可怕的是,你习惯镜头不看见你——你成了背景,被无害化地擦掉。

我认识一个修机的老匠,他告诉我:镜头若长期不拍,会生霉;若只拍一种,霉会长在眼里。他说这话时,用布擦自己的眼镜,布上落下灰,灰里有微小的光点。光点像水里的盐,尝不出味,却让水有了性格。

后来,事情如你所知:有人来敲门,镜头被装袋,名字被装进另一只袋。袋子有口,口上有绳,绳扎得紧。紧到什么程度?紧到舌头也跟着打结。于是传媒上出现了一种新句法:被动、抽象、无名。它们像三位德高望重的老师,教你如何把一个夜晚改写为“某地某时发生情况”,再把“人”改写为“有关人员”,把“看见”改写为“据称”。据称久了,连据称的人也开始据称自己。

可镜头的温度不是据称。它是当时、当场、当面——是风经过玻璃时起的那一层雾,是手心因为握紧而出的一点汗。温度一旦存入画面,就像把手印按进湿泥,干了也在。有人想磨掉,于是派来一队解释,拿着抛光机,对着泥印一顿打磨。打磨的声音不小,像一支乐队在演出。演出结束,台上很亮,台下很暗。亮处说:看,地面整洁如新;暗处却有人摸索到一道浅浅的凹,像一只没化好的皱纹。

我去看过那条街。白天,行人稀少,咖啡馆里的杯子很薄,薄到几乎听得见指尖摩挲的“沙”。我坐在靠窗的位置,窗外风把落叶翻了一遍又一遍,翻到背面,背面还是叶。柜台上的电视在放新闻,新闻说“秩序井然”。井然两个字落地很稳,稳得连杯垫都不偏。偏的是我心里那颗螺丝,拧得太紧,咬住不松。我把杯子端起来,照着窗口,杯里倒映出街对面一扇门——有人曾在那扇门后按下REC。现在门关得严丝合缝,像纸封了一层漆。

我忽然想到,那镜头拍下的并不只是人群,是时间。时间通常无影,镜头给它找了一件外套:冷、亮、白。穿上外套的时间被递给我们看,我们接在手里,有的人手心热,有的人手心凉。我不知那位举镜的人此刻手心什么温度,只知他的名字被许多嘴说过,又被许多句式吞回。吞回去的名字会去哪儿?大概落进嗓子后面那条狭窄的沟,和咽口水的动作挤在一起,时不时哽一下。

写到这,我本想抒一口气,偏偏气卡在肋下,进退两难。于是想起一个笨法子:把镜头比作灯。灯不必须照亮正义,灯只负责让你看清屋里的家具——沙发在左,桌在右,门在正对面,谁坐下、谁站起、谁绕到镜头背后去了。看清之后,你还是可以选择不开口;不开口,不等于没看见。灯的温度来自灯丝,灯丝细,易断。灯一旦灭,屋里的人会说:本来也没什么可看的。我不劝他们,我只在门框上摸了一把,那儿有一道极浅的划痕,像曾被谁急急忙忙抓过一次。

我收好笔,像把镜头收入袋。与那只“被收入”的袋不同,我这只袋没有绳子,只有一枚扣。扣很松,风一吹就开。开了也不紧要,稿纸会翻一页,白页露出来,白得像一面微型的幕。幕上没有影,只有温度。温度看不见,摸得着。你若把手心贴上去,会觉得它不烫,只是暖。暖到什么程度?暖到记忆还敢伸手,暖到夜里也不太冷。至于更多,我不说了。说多了,镜头要起雾。雾里的人看起来都像好人,这不好。

若你问,镜头究竟该几度?

我答:不冷不热,正好烫手。

烫一下,便知还活着。

The Pandemic Trilogy (III) — After the Film

Abstract: In the winter of 2022, there was a lens that refused to cool down. It was raised in the streets, higher than a blank sheet of paper. Others raised slogans, it raised an aperture; others chanted banners, it clicked shutters. I suddenly realized, what the lens captured was not only the crowd, but time itself. Time is usually without shadow, and the lens found it a coat: cold, bright, white.

Author: Zhang Zhijun

Editor: He Qingfeng

Responsible Editor: Luo Zhifei

Translation: He Xingqiang

“There are two things in this world most afraid of heat: lies and lenses. The moment the palm warms, both begin to drip.

A lens is cold. When it leaves the factory, its heart is nothing but glass and metal. Only when held in the hand, pressed against skin, does it begin to warm. Where does that warmth come from? From palms, from breath, from inconvenient curiosity. Some dislike this warmth, believing that a heated lens is like an inflamed eye—it reveals things that shouldn’t have grown. And so they propose to cool the lens: cover it, seal it, cut its power, forbid its use. Once chilled enough, the lens learns to ‘self-destruct’: shooting only landscapes, flowers, and smiling faces at ceremonies.

But in the winter of 2022, there was a lens that refused to cool. It was raised in the streets, higher than white paper. Through it, wind blew east to west, people moved south to north, and lights shone brighter and brighter. The lens did not speak; sounds crashed into it from all directions and slipped silently out its back. It was only a hole, yet it remembered better than many mouths.

I saw the man holding it. He walked slowly, as if afraid to step on shadows. Others raised slogans, he raised an aperture; others shouted banners, he pressed shutters. His shoulders were not broad, yet the strap upon them was steady—one end tied to the lens, the other to his little-known name. That name became known later, because the lens had gathered warmth—and warmth causes trouble.

I often wonder, why does the lens cause trouble? Because it remembers too much. It remembers the tremor of a hand in the crowd, a raindrop on the edge of paper, the flash of vigilance fleeing one pair of eyes and rushing back into another. The lens is a faithful narrator, too faithful to delete “irrelevant” tremors and hesitations. Those who refuse to delete are often deleted themselves. So, the lens was bagged, the name pressed against a desk. The one pressing smiled: “It’s just procedure, don’t worry.”

Procedure is gentle. It makes coldness sound justified. Cold has many advantages: equipment lasts, records stay orderly, explanations need not tire. Only the street drops to zero degrees. Below zero, many breaths no longer show as mist, so it seems there are none. A city without breath sleeps heavily—like a stone sinking to the lake bottom, without bubbles, startling not even a fish.

Some say: “A lens has no stance, it is only optics.” True, and not true. A lens merely admits light, but light always falls on someone’s face. In that instant, a stance is born, even without declaration. When the lens points at weeping, weeping has a place; when it points at laughter, laughter has a scale. More often, the lens points at waiting—waiting in lines, for tests, for codes, for scanning. Wait long enough, and people forget what they wait for, so the lens remembers for them. The most frightening thing is not that the lens sees you, but that you grow accustomed to being seen by it; worse still, that you grow accustomed to not being seen by it—you fade into the background, harmlessly erased.

I knew an old repairman. He told me: if a lens lies unused too long, it grows mold; if it shoots only one kind of thing, the mold grows in the eyes. As he spoke, he wiped his glasses. The cloth caught specks of dust, and in the dust glittered tiny points of light. Like salt in water—tasteless, yet giving water its character.

Later, events unfolded as you know. Someone knocked at the door, the lens was bagged, the name put in another bag. The bag had a mouth, tied with a cord—tied so tight the tongue knotted with it. Thus, the media birthed a new grammar: passive, abstract, anonymous. Like three venerable teachers, they taught how to rewrite a night into “an incident occurred at a certain place and time,” how to turn “a person” into “relevant personnel,” how to turn “saw” into “reportedly.” Repeat “reportedly” long enough, and even the person reported begins to “reportedly” themselves.

But the warmth of a lens is never “reportedly.” It is immediate, present, face-to-face—the fog forming when wind brushes glass, the drop of sweat from a tightened palm. Once preserved in an image, warmth is like a handprint pressed into wet clay—it hardens, but remains. Some try to grind it away, sending in a team of interpreters with polishing tools, scouring the mark with a noise like a band performance. When the show ends, the stage is bright, the audience dark. The bright say: look, the floor is spotless. But in the dark, someone runs their hand over a faint groove, like a wrinkle that never smoothed.

I visited that street. By day, few passersby. The cups in the café were so thin you could almost hear the sand of fingertips sliding over them. I sat by the window. Outside, the wind flipped fallen leaves again and again—their backs, still leaves. On the counter, the TV played the news: “orderly and stable.” The words landed so firmly, even coasters didn’t budge. What shifted was the screw in my heart, wound too tight to release. I lifted my cup toward the window. Reflected in the glass was a door across the street—once, someone had pressed REC behind it. Now it was shut, sealed as if lacquered over paper.

And I thought again: what that lens captured was not only people, but time. Time, usually invisible, was given a coat by the lens: cold, bright, white. Time clothed, handed to us. Some palms warm, some palms cool. I do not know the temperature of the palm holding that lens now, only that his name was spoken by many mouths, then swallowed back by many phrases. Where do swallowed names go? Likely down the narrow throat-gully where gulps of water squeeze, sometimes choking on the way.

Writing this, I tried to breathe out—but the breath stuck under my ribs, unable to move. Then I thought of a clumsy comparison: a lens is like a lamp. A lamp need not shine for justice; it only shows the furniture in the room—sofa left, table right, door ahead, who sat, who rose, who slipped behind. After seeing, you may still choose silence. Silence does not mean unseen. The lamp’s warmth comes from its filament—thin, fragile, breakable. Once the light dies, the people inside will say: there was nothing to see anyway. I do not argue. I only touched the doorframe. There, a shallow scratch remained, as if someone once grasped it in haste.

I put away my pen, as if tucking a lens into its bag. Unlike the “confiscated” bag, mine had no rope, only a clasp—loose, easily opened by a gust. No matter: the manuscript will turn a page, revealing a blank one, white like a miniature screen. No shadow upon it, only warmth. Warmth invisible, but tangible. If you press your palm against it, you’ll find it not scalding, only warm. Warm enough that memory dares reach out; warm enough that the night isn’t too cold. Beyond that, I’ll say no more. Say too much, and the lens fogs. In the fog, everyone looks like a good person—that isn’t good.

If you ask: what temperature should a lens be?

I answer: neither cold nor lukewarm, but hot to the touch.

Hot enough to know you’re still alive.

疫情三部曲(二)——人声鼎沸

作者:张致君

编辑:何清风 责任编辑:罗志飞 翻译:吕峰 校对:冯仍

“人群里并无喉舌,只有被迫的气息;可气息一齐吐出,便比锣鼓更整齐。”

我常想,人群的声音从哪里来?从喉头?从胸腔?都不是。真正的声音,常从禁声处长出来——像石缝里的草,越压越硬,越割越锋利。

那三年里,城在罩子底下,人人学会用“安静”表态。安静久了,嗓子像收了一张欠条,欠条上没有数字,只有一个“随时”。于是人说话之前,先掂量“随时”,说到一半,便打住:小心。但有一种声音不掂量,它从缝里钻出,借谁的口都不重要——重要的是,空气里第一次听见了“人”的回声,而不是告示、通报、喇叭、口号。

起初,声音很小,像针落在棉上。有人在窗口和猫说话,有人在电梯里和镜子说话,有人在核酸队伍里和鞋带说话。说着说着,忽然发现鞋带是聋子,猫是哑巴,镜子只会复述。那晚之后,声音才找到同伴:一张举起来的白纸,响过任何字。

许多人以为人群的声音一定嘈杂,其实不然。那晚,我走在“中路”,人很多,声却不乱。有人低声唱旧歌,不唱到高音;有人念被删掉的句子,不念到句号;有人举起无字的牌子,让风替他读。最吵的其实是路灯和摄像头,它们嗡嗡作响,好像蜂巢被惊动了。蜂巢怕烟,人群怕什么呢?怕的不是警棍,也不是冬夜——怕的是第二天的解释把这一夜解释没了。

解释是一门雄壮的学问,擅长把“看见”改写为“误会”,把“参与”改写为“围观”。它像一辆勤劳的清运车,天不亮就出来,把街上的脚印一并铲走,扫把收尾,水车一浇,天地清白。可是我知道,铲不掉的那一层在鞋底,水冲不掉;更有一层在嗓子眼里,吞不下去。

我在路口看见两个青年,一男一女,像刚下晚自习。他们没有喊,只站在军队的面前。男的手抖,女的眼稳。一个年纪较长的男人路过,皱眉:“别闹。”女孩子点点头:“我们不是闹,我们只是想把声音拿出来晒晒。”男人叹口气,走远。后来我才明白,他不是反对声音,他是怕声音受潮——受潮的声音会发霉,霉里长出麻烦。

不久,果然下雨。雨是公告做的,细、密、勤。它滴在词上,滴在传言上,也滴在真相上。人们把纸收起,放进书里,书又放进抽屉。抽屉一关,里面响了一声很轻的“哑”。从此,许多人改学“点头”,点头不湿,点头也不响。唯有我偶尔把抽屉拉开一指宽,让一条缝透气。缝里有旧夜的气味——冷、醒、干净。

人群的声音不是谁的私产,这点叫管理的人很苦恼。他们爱按片区分配:此片唱赞歌,彼片讲故事;这一段齐步走,那一段齐步站。可声音像水,遇到缝就流,遇到墙就绕,遇到堵死的地方,便往土里渗。渗久了,地皮会湿;地皮一湿,草就要出来。于是有人忙着铺石板,把草根一并压住,再竖一块牌子:此处不宜生长。牌子立得多了,城里绿地反而多起来——全是牌子做的绿。

有一天,广场上出现几叠小小的音符,是谁匆匆写下,没来得及用。它们像迷路的蚂蚁,一会儿排成字,一会儿散成沙。我蹲下看,认出几个旧时的词:发问、讨论、辩驳、批评。它们在风里打颤,像一桌冷掉的饭。我伸手想把它们捧起来,忽然一阵“噤声”的风吹过,音符四散,落在每个人的袖口里。袖口立即严实起来,像给心口加了一道围巾。

人群的声音还有一种,叫“沉默中的同意”。这同意不是投票,是交换:你不说,我也不说;你不看,我也不看;大家都不知道,便等于没发生。久而久之,不说话的人越来越多,说话的人越来越少。少到什么地步呢?少到连“沉默的人”也要找个沉默的人作证,证明他一直沉默。于是出现一种新职业:沉默鉴定师。他站在你旁边,看你三秒钟,便盖章:沉默合格。盖多了章,他的手生起老茧,茧里也有声音——是硬度太高时发出的摩擦。

我问一位朋友:“你那天去了么?”他说:“我在网上围观了。”我又问:“看见什么?”他说:“看见很多人被看见。”

我想了想,这句倒也公道。被看见是人群的第一课,第二课是互相看见,第三课才轮到“听见”。那晚,我们学到第二课;至于第三课,老师尚未到场——或者已经到场,只是不发声。

后来,城恢复“秩序”。秩序是一张整洁的桌布,盖住桌面上潦草的划痕。人群散去,石榴花谢,路灯继续亮。人们相互点头,像从同一部手册里学出来的礼貌:不提问,不追忆,不泼冷水。只是每当夜深,风从街角拐进来,总会碰掉一两句压低了的词,它们滚在路沿边,叮叮当当,像迷你钟。钟不大,却提醒得很准:那晚并非梦。

至于那一夜之后的“人群之声”,有人在档案上给它另取了名字,名字很长,读完要喝水。我懒得背,依旧称之为“声”。声在,不必多说。声若不在,多说也无用。写到这里,我忽然自笑:一篇讲“人群之声”的文字,竟大半时光在讲沉默。可这并不矛盾——真正的声,往往从沉默里出;真正的沉默,也常被声照了一下脸。

我把稿纸翻过来,背页空白。空白上风正好。

我用指腹轻轻一抹,像摸一个孩子的头,摸到了微小的涌动:那不是话,那是气。气在,便有声;声在,便有人。而我不会收笔。

The Pandemic Trilogy (II) — The Clamor of Voices

Abstract:There is a kind of sound in crowds called “consent in silence.” This consent is not a vote but an exchange: you don’t speak, I don’t speak; you don’t look, I don’t look; if nobody knows, it’s as if nothing ever happened. Over time, fewer and fewer people speak, and more and more remain silent.

By Zhang ZhijunEdited by He Qingfeng · Responsible Editor: Luo Zhifei Translator:Lyu Feng

“There is no mouthpiece in the crowd, only forced breath; but when breath is exhaled together, it is louder than drums.”

I often wonder: where does the sound of the crowd come from? The throat? The chest cavity? Neither. True sound grows from silence — like grass in cracks of stone, the more pressed, the harder it grows; the more cut, the sharper it becomes.

During those three years, the city was trapped under a cover, and everyone learned to use “quiet” as expression. Silence, after long practice, felt like a debt slip pressed into the throat — no number written on it, only the word “anytime.” So before speaking, one weighed that anytime, and halfway through words, cut them off: be careful. Yet some voices never weighed, slipping out through cracks. Whose mouth they borrowed didn’t matter — what mattered was that for the first time, the air carried the echo of people, not notices, broadcasts, or slogans.

At first, the voices were small, like a needle falling on cotton. Someone whispered to a cat at the window, someone talked to a mirror in the elevator, someone muttered to shoelaces in the testing queue. But shoelaces are deaf, cats are mute, mirrors only repeat. Only that night did voices find companions: a sheet of blank white paper, louder than any printed word.

Many imagine the sound of crowds must be noisy. In fact, it isn’t. That night, I walked on “Central Road.” There were many people, yet no chaos. Someone softly sang an old song, never reaching the high note; someone recited deleted lines, never reaching the full stop; someone lifted a wordless placard, letting the wind read it. The loudest things were the streetlights and cameras, buzzing like disturbed hives. Smoke frightens bees. What frightens the crowd? Not batons, nor winter nights — but the next day’s explanations erasing the night before.

Explanation is a grand discipline, skilled at rewriting “I saw” into “I misunderstood,” and “I joined” into “I merely watched.” Like a tireless sanitation truck, it came out before dawn, sweeping away footprints, rinsing streets into spotless blankness. Yet I knew some layers could not be scraped away — they stuck to soles, they lodged in throats, impossible to swallow.

At an intersection I saw two youths, a boy and a girl, as if just out from evening study. They didn’t shout, only stood before the military line. The boy’s hand trembled, the girl’s eyes were steady. An older man passed by, frowned: “Don’t make trouble.” The girl nodded: “We’re not making trouble, we just want to let our voices out to dry.” The man sighed and walked away. Later I understood: he wasn’t against voices — he feared they’d grow damp. Damp voices mildew, and mildew breeds trouble.

Not long after, it rained. Rain made of announcements — fine, dense, persistent. It fell on words, on rumors, on truths. People folded up their papers, tucked them in books, hid the books in drawers. When the drawers closed, there was a faint “mute” inside. From then on, many switched to nodding. Nods don’t get wet, nor make sound. Only I sometimes left my drawer a crack open, letting in a breath of old night — cold, sober, clean.

The sound of the crowd is not anyone’s private property — which vexes those in charge. They prefer allocation: this district sings praises, that one tells stories; this block marches, that one stands still. But sound is like water: it flows through cracks, bends around walls, and seeps into soil if blocked. Long enough, the ground grows damp, and grass pushes out. So some hurry to lay slabs, pressing roots flat, erecting signs: No Growth Here. With so many signs, the city grows strangely green — green made of warnings.

One day, I saw stacks of tiny musical notes scattered in the square. Someone had written them hastily, left them unused. They crawled like lost ants, sometimes forming words, sometimes dissolving into dust. I bent down and recognized old terms: questioning, debating, criticizing. They shivered in the wind, like a table of cold leftovers. I reached to gather them, when a gust of silence blew, scattering them into every cuff. Sleeves immediately tightened, wrapping the chest like an extra scarf.

There is another sound of the crowd, called “consent in silence.” This consent is not voting, but exchange: you don’t speak, I don’t speak; you don’t look, I don’t look; if none of us knows, it equals never happening. Over time, fewer and fewer speak, more and more remain silent. Until what degree? Until even the “silent ones” must find another silent one to certify that they have always been silent. Thus emerged a new profession: certified silence inspector. He stood by you, watched three seconds, stamped: Silence qualified. Stamp enough times, and calluses formed on his palm — and even the callus had a voice, the friction of too much hardness.

I asked a friend: “Were you there that day?”He replied: “I watched online.”I asked: “What did you see?”He said: “I saw many people being seen.”

I thought, that was fair. To be seen is the first lesson of crowds; the second is to see each other; the third is to hear. That night, we learned the second lesson. As for the third, the teacher had not yet arrived — or perhaps had arrived, only chose silence.

Later, the city “returned to order.” Order is a neat tablecloth, covering messy scratches beneath. The crowd dispersed, pomegranate blossoms fell, streetlights stayed on. People nodded at each other, like manners copied from the same manual: no questions, no memories, no cold water. Only at night, when wind turned a corner, it would knock loose a word or two, rolling along the curb, clinking like a tiny clock. A small clock, but precise: that night was no dream.

As for the “voice of the crowd” after that night, some renamed it in archives, a title so long it needed water to finish reading. I can’t be bothered to memorize. I still call it “voice.” If voice exists, little more needs saying. If it doesn’t, saying more is useless. Writing this, I laughed at myself: a piece on the voice of the crowd spent half its time on silence. But that is no contradiction — true voice often grows out of silence; true silence is often lit briefly by voice.

I turned the manuscript over. The back was blank. The wind passed just right. I brushed it with my fingertip, like stroking a child’s head, and felt a tiny stirring: it wasn’t words, it was breath. Where breath is, there is voice; where voice is, there are people. And I will not put down the pen.

疫情三部曲(一)——纸上无字

作者:张致君

编辑:何清风 责任编辑:罗志飞 翻译:程铭 校对:冯仍

“写字要胆子,擦字要钉子;故而最响的,常是那张什么也不写的纸。”

我向来不信天灾能连续三年。天灾不过一口气,人祸才是长命烟。三年前,城门忽然合拢,门缝里吐出几张告示,字迹大得像春联:为了大家好。大家于是各自回家,把门反锁,把窗钉死,把嘴巴也用胶纸贴上。街心的石榴树照开,开得像无声的火,可那火只用来照花名册——谁出门谁回家,几时出、几时回,门口摄像头一睁一合,像庙里的钟。庙钟不问人,只问规矩。

规矩日日更新,比天气还勤快。昨日可以下楼做核酸,今日不行;昨日核酸阴的可以上班,今日也不行;昨日“静默”,今日“再静默”。我见过邻居家乳名“壮壮”的孩子隔着铁栏杆冲我笑,牙缝里卡着面包屑。第二天他不笑了,栏杆那头多了一块红纸,上写:封。第三天,壮壮与红纸一起不见了。我本想问问,可问话需要出门,出门需要通行证,通行证需要理由,而我没有“必要的理由”。于是我把嘴角的面包屑抠掉,仍然沉默。沉默也是一种通行证,还是万能的。

我在窗里数日光,光像一枝没气的铅笔,时粗时细。偶有刺耳的喇叭车驶过,喇叭喊话,声音一半像劝、一半像审:“不要聚集,不要传播,不要思考——哦,不,是不要信谣。”我便想起古书里说的“绝学无忧”,此处稍作改良:绝言无忧。无忧久了,连梦也变得安静,梦里人都戴着口罩,彼此点头,点头算是最大的风流。

直到有一夜,风忽然换了方向。西北城传来火光,火光里有人喊娘,喊得嗓子像被门扣住。第二天城里贴出讣告,字仍旧很大,意却很小:一切正常。可街心的石榴花却在风里乱跳,像谁掌心攥紧又张开——张开的,是一张白纸。白纸没有字,偏生最吵。它越空,人的心里越满;它越轻,人的脚步越重。于是许多人走到路灯底下,举起那一张空白,像举起一口无名的碑。碑不写字,写字就要被涂黑;碑不雕像,雕像就要被推倒。人们便举空白,空白里有他们不敢写、也来不及写的全世界。

我也去了。不是去写,而是去看。乌鲁木齐、长安、广场、河边,每一座城都有一条街叫“中路”,因为它们都在我们心里正当中。年轻人站在那儿,像新磨的刀——不是要砍谁,只是想照照自己到底长成了什么样。他们唱歌,有人把歌词吞回肚里,只把曲调扔给夜风;他们说话,有人把名字藏在口罩里,只把眼睛亮给摄像头。我看见一位姑娘举纸的手在抖,纸也抖,纸上的无字便像千百个小黑字在跳。旁边有个小伙子笑,她问笑什么,他说:“我第一次拿起纸,发现比拿起任何东西都沉重。”

我知道,这一夜之后,白纸会被没收——不是从手里收,而是从记忆里收。收走以前,总得先装裱。于是城里忽然勤快,忙着给每张纸加框、给每双眼睛加帽。帽子上有字:聚集,煽动,扰乱,寻衅。字多了,纸就轻了,手也空了。它们要把一夜的火,改写成一阵风,风吹过,叶落尽,树还在。树在,是为了明年再开石榴花,好让人误以为这一切周而复始,天下太平。

不过,还有人不太识相。他带了台不大不小的机子,站在路灯和白纸之间,用镜头把夜色一寸寸折叠,叠成一部我要叫它“人眼的备忘录”的东西。他不喊口号,也不挑灯火,只让街上的脚步自己响,让纸边的沉吟自己长。他只是把“看见”这件事,照相了。后来我才知道,他姓陈,名字像雨后的玻璃:品霖。玻璃最怕被敲,可也最爱反光。他把那夜的风映在玻璃上,玻璃便有了温度。可温度一高,玻璃就容易碎。果然,没多久,有人来敲门;门开了,他的机子被装进袋子里,他的人被装进另一只袋子——袋子叫“手续”。手续走得很快,说辞走得更快:上传、传播、寻衅、滋事。四个词像四颗钉,把一个拍过“空白”的人钉在文件上。文件夹厚得像城墙,城墙外头,石榴花照旧开。

有人问我:你看这些年,总算是“解封”了不是?我笑笑。解封像拆创口贴,贴久了,皮都跟着走。门上的白条撕了,心上的那一道还粘着。那道看不见的封条更牢,它把许多夜晚封在我们喉咙里,遇到风就勒一下,提醒你:别抬头,别出声,别做梦。若一定要做,做个省油的梦——梦见排队,梦见核酸,梦见“为你们好”。梦醒了,手机里还会跳出提醒:今日新增零、社会面零、舆情零。零真是好字,圆滑,没有棱角,塞进任何缝里都不硌人。只是被零包围久了,人也就学会了把自己削成一个零,恰好镶进缝隙,彼此安之若素。

我偶尔也去街上走。街上新换的路灯又白又冷,照得人影像没栽稳的树。有人把那一夜剪成了短视频,发上去,像把纸鸢放进天井。天井很高,风也很高,可除了四面墙,再没有云。纸鸢绕了一圈,线被人轻轻一扯,稳稳落回地面,落在“违规”的标签上。贴标签的手很熟练,像老裁缝缀扣子,找准洞眼,一戳、一拉,一颗扣子就端端正正系在你胸口。你若觉得勒得慌,它会说:“这是为了体面。”

体面原来也分配。分配像口罩,一人一只,罩住不同的脸,露出同样的沉默。有时我看见公交站里的告示牌,镜面反光,反出来的不是广告,而是几年前空荡荡的车站——那时候车并不空,是城在空。空城的风喜欢说话,可风后来也学会了避嫌;它绕开人群,去吹没有备案的草。

我也想过写点什么。写字是一种坏习惯,像咳嗽,会传染。有朋友劝我别写,写了也别发,发了也别贴真名。我说好。于是我改了个名字,像给尸体化妆。化完妆的尸体看着舒服,大家都敢靠近。只是我写着写着,笔尖沾上一点冷汗——那是纸渗出来的。纸是白的,汗也是白的,干了就不见。我把汗吹干,继续写。写到后来,忽然觉得这文章最好什么也别写,空着。空着的文章像那张纸,既省事,又省命。我便在页眉打一行字:此处无字。页脚也打一行:此处更无字。如此一来,上不言,下不语,中间的沉默就像一枚硬币,两面都是真。

陈君的纪录片里有很多人,举纸的,不举的;唱歌的,闭眼的;走过的,停下的。我也混在里头,像一滴水混进水里。后来他被带走,我才猛然觉得嗓子有点沙,像吞进一粒玻璃渣。医生说多喝水。我确实渴,可水越喝越干,像从石头缝里挤出来的。人说时间能磨平一切,我看未必。时间只是把凸起磨成不痛的形状,叫你忘了它还卡在肉里。等你翻身的时候,它又硌了一下,你便知道,三年的封门没有真的过去,白纸也没有真的过去,甚至连那台机子里微微发热的芯片,都没有过去。它们化在空气里,像看不见的粉尘,时不时被呼吸带出来,又被我们自己咽回去。

有人要我给这几年下个名字。我不敢。起名是种权力,权力是种病,它爱把复杂的痛,简化成方便的药名。我只好照旧,用一张纸,白纸。纸不说话,可它在风里翻动,就像一只手从水底探上来,摸到谁算谁。摸到我时,我把它按回去,笑道:别闹。按下去的那一刻,我听见远处像有人在敲门。敲了三下,又三下。门没有开,心先开了一条缝。缝里有一点光,像石榴花刚要绽。花开得慢,慢到足以让人误会它根本没开过。可我知道——它开过。开过一次,就够我一辈子记。

到这里,本可收笔。可我又想起那些喜欢“为我们好”的人,他们最怕的不是谣言,是记性。记性像草,禁了还长。于是我决定把记性放进一个无字的匣子里,贴上标签:无害。倘若有朝一日,有人问起:那一夜,你们见了什么?我便把匣子递过去,叫他自己照一照,匣子里有他,也有纸,也有镜头。镜头的玻璃反射出一张脸,脸上既没有口号,也没有笑,只有一对眼睛——不是怒,是醒。

醒来的人不一定说话。醒只做两件事:把窗打开,和把灯关小。窗打开,风就进来;灯关小,影子就不那么吓人。至于别的,我不敢想,也不敢教。教人是危险的行当,尤其在一个连风都要备案的地方。便这样吧。我写到这里,停笔,像医生把刀从伤口里慢慢抽出来,刀是冷的,血是热的,二者互相谁也不服。等它们自己去交涉,我只把纱布按住,再叮嘱几句:别跑跳,别哭闹,别去看热闹。因为看热闹的人,迟早也会变成热闹里被看的人。

纸上无字,字在纸外。

你若要看,抬头;你若不看,低头。

抬头有风,低头有土。

二者之间,刚好够一张纸通过。

Epidemic Trilogy (I) — No words on paper

Abstract: Urumqi, Chang’an, Square, Riverside, every city has a street called “Zhonglu”, because they are all right in our hearts. There are many people in Chen Jun’s documentary, those who raise the paper and those who don’t raise it; those who sing, those who close their eyes; those who walk by, those who stop. Teaching people is dangerous, especially in a place where even the wind needs to be filed.

Author: Zhang Zhijun

Editor: He Qingfeng Responsible Editor: Luo Zhifei Translator:Ming Cheng

“It takes courage to write, and it takes nails to wipe words; therefore, the loudest thing is often the paper that doesn’t write anything.”

I have never believed that natural disasters can be for three consecutive years. Natural disasters are just a breath, and man-made disasters are the long-lived smoke. Three years ago, the city gate suddenly closed, and several notices were spit out in the crack of the door. The handwriting was as big as the Spring Festival couplets: For everyone’s good. So everyone went home, locked the door, nailed the window, and put glue paper on their mouths. The pomegranate trees in the heart of the street bloom like a silent fire, but the fire is only used to illuminate the flower list – who goes out and goes home, when they go out, when they come back, and the camera at the door opens and closes, like the clock in the temple. The temple bell does not ask questions about people, but only about rules.

The rules are updated day by day, which is more diligent than the weather. Yesterday, I could go downstairs to do the nucleic acid test, but today I can’t; yesterday, I could go to work if the nucleic acid was negative, but I can’t do it today; yesterday it was “quiet”, and today it’s “quiet again”. I have seen a neighbor’s child with the name “Zhuang Zhuang” smiling at me through the iron railing, with breadcrumbs stuck between his teeth. The next day, he stopped laughing. There was an extra piece of red paper at the end of the railing, which said: seal. On the third day, Zhuang Zhuang disappeared with Hong Zhi. I wanted to ask, but I need to go out, I need a pass to go out, and I need a reason for the pass, but I don’t have a “necessary reason”. So I took off the breadcrumbs from the corners of my mouth and remained silent. Silence is also a kind of pass, and it is omnipotent.

I spent a few days in the window, like a dead pencil, sometimes thick and sometimes thin. Occasionally, a harsh horn car passed by, and the horn shouted, half of which sounded like advice and half like a judge: “Don’t gather, don’t spread, don’t think – oh, no, don’t believe the rumors.” I thought of the ancient book saying “no worries about learning”, which is slightly improved here: no worries. After worrying for a long time, even the dream became quiet. The people in the dream were wearing masks and noddding to each other. Noding is the biggest trend.

Until one night, the wind suddenly changed direction. There was a fire in the northwest city. In the fire, someone shouted mother, and his voice seemed to be held by the door. The next day, an obituary was posted in the city. The words were still large, but the meaning was small: everything was normal. But the pomegranate flowers in the center of the street are jumping in the wind, like someone’s palms are clenched and opened – open, it is a blank sheet of paper. There are no words on the blank paper, and it is the most noisy. The more empty it is, the fuller the heart is; the lighter it is, the heavier the pace. So many people walked under the street lamp and held up the blank sheet, like a nameless monument. If the stele is not written, the writing will be blackened; if the stele is not a statue, the statue will be pushed down. People cite the blank space, and there is a world that they dare not write and have no time to write about.

I also went. Instead of writing, I went to see it. Urumqi, Chang’an, Square, Riverside, every city has a street called “Zhonglu”, because they are all right in our hearts. The young man stood there, like a newly sharpened knife – not to cut anyone, but just to see what he had grown up to. They sang, some swallowed the lyrics back into their stomachs, and only threw the melody to the night wind; they talked, some hid their names in masks, and only showed their eyes to the camera. I saw a girl’s hand shaking when she held the paper, and the paper was also shaking. The words on the paper were like thousands of small black words jumping. There was a young man next to him laughing. She asked why he was laughing. He said, “The first time I picked up the paper, I found that it was heavier than anything else.”

I know that after this night, the blank paper will be confiscated – not from the hand, but from the memory. Before taking it away, you have to frame it first. So the city suddenly became diligent, busy adding frames to every piece of paper and hats to every pair of eyes. There are words on the hat: gather, incite, disturb, quarrel. With more words, the paper is lighter and the hands are empty. They want to rewrite the night’s fire into a gust of wind. The wind blows, the leaves fall, but the trees are still there. The tree is here to bloom pomegranate flowers next year, so that people mistakenly think that all this is repeated and the world is peaceful.

However, there are still people who don’t know each other very well. He took a large machine, stood between the street lamp and the white paper, folded the night inch by inch with the lens, and folded it into something I would call the “memo of the human eye”. He didn’t shout slogans or pick up lights. He just let the footsteps on the street sound by himself, and let the pondering on the paper grow by itself. He just took a picture of the “seeing” thing. Only later did I know that his surname was Chen, and his name was like the glass after the rain: Pinlin. Glass is most afraid of being knocked, but it also likes to reflect light. He reflected the wind of that night on the glass, and the glass became warm. But when the temperature is high, the glass is easy to break. Sure enough, not long after, someone knocked on the door; the door opened, his machine was put into a bag, and his people were put into another bag – the bag called “procedures”. Procedures go quickly, and rhetoric goes faster: uploading, spreading, quarreling, causing trouble. Four words are like four nails, nailing a person who has taken a “blank” to the file. The folder is as thick as a city wall. Outside the city wall, pomegranate flowers bloom as usual.

Someone asked me: You see, these years have finally been “unblocked”, right? I laughed. Unsealing is like removing the wound sticker. After pasting it for a long time, the skin will follow. The white stripe on the door was torn, and the one on the heart was still stuck. The invisible seal is firmer. It seals many nights in our throats. When we encounter the wind, we will strangle it and remind you: don’t look up, don’t make a sound, don’t dream. If you must do it, have a dream of saving fuel – dreaming of queuing, dreaming of nucleic acid, dreaming of “good for you”. When you wake up, a reminder will pop up in your mobile phone: zero new additions today, zero social face, and zero public opinion. Zero is really a good word. It’s smooth, has no edges, and it won’t be hard to put into any crack. It’s just that after being surrounded by zero for a long time, people have learned to cut themselves into a zero, just put them in the gap, and feel at ease with each other.

I also go to the street occasionally. The newly changed street lights on the street are white and cold, shining on the trees that are not stable. Someone cut that night into a short video and sent it up, like putting a paper kate into the patio. The patio is very high and the wind is also very high, but there are no clouds except for the four walls. The paper kite circled around, and the thread was gently pulled by someone, fell steadily back to the ground, and fell on the label of “violation”. The hand that affixes the label is very skillful, like an old tailor who decorates a button, finds the hole, pokes and pulls, and a button is tied to your chest. If you feel panicked, it will say, “This is for decency.”

Denemness is also distributed. The distribution is like a mask, one for each person, covering different faces and showing the same silence. Sometimes I saw the notice board in the bus stop, and the mirror reflected the light. Instead, it was not an advertisement, but an empty station a few years ago – at that time, the car was not empty, but the city was empty. The wind in the empty city likes to talk, but the wind later learned to avoid suspicion; it bypassed the crowd and blew the unrecorded grass.

I also want to write something. Writing is a bad habit, like coughing, which can be contagious. Some friends advised me not to write, not to post even if I wrote, and not to post my real name. I said yes. So I changed my name, like putting makeup on a corpse. The corpse after makeup looked comfortable, and everyone dared to approach it. It’s just that I wrote, and the tip of the pen was stained with a little cold sweat – it was seeping out of the paper. The paper is white, and the sweat is also white. It will not be seen when it is dry. I dried my sweat and continued to write. After writing, I suddenly felt that it was better not to write anything about this article, but leave it blank. Empty articles are like that paper, which saves both trouble and life. I typed a line on the header: There is no word here. Also type a line in the footer: there are no words here. In this way, the upper side is silent, the lower side is silent, and the silence in the middle is like a coin, and both sides are true.

There are many people in Chen Jun’s documentary, those who raise the paper and those who don’t raise it; those who sing, those who close their eyes; those who walk by, those who stop. I’m also mixed in, like a drop of water mixed into the water. Later, he was taken away, and I suddenly felt that my throat was a little sandy, like swallowing a glass slag. The doctor said to drink more water. I’m really thirsty, but the more I drink the water, the dryer it gets, like it’s squeezed out of a stone. People say that time can flatten everything, but I don’t think so. Time just grinds the bulge into a painless shape, so that you forget that it is still stuck in the meat. When you turned over, it shook again, and you knew that the three-year door closure had not really passed, the white paper had not really passed, and even the slightly hot chip in the machine had not passed. They melt into the air, like invisible dust, brought out by breath from time to time, and swallowed back by ourselves.

Someone asked me to give a name for these years. I don’t dare. Naming is a kind of power, and power is a kind of disease. It likes to simplify complex pain into convenient medicine names. I had to use a blank sheet of paper as usual. The paper doesn’t speak, but it turns over in the wind, just like a hand coming up from the bottom of the water, touching whoever it is. When it touched me, I pressed it back and said with a smile: Don’t make trouble. The moment I pressed it down, I heard someone knocking on the door in the distance. Knocked three times, three times again. The door didn’t open, and the heart opened a slit first. There is a little light in the gap, like a pomegranate flower that is about to bloom. The flower blooms slowly, so slowly that people misunderstand that it has never bloomed at all. But I know – it has been opened. Once I drive it, it’s enough for me to remember for a lifetime.

At this point, I could have collected the pen. But I also thought of those who like “for our good”. What they are most afraid of is not rumors, but memory. The memory is like grass, and it is still long after prohibition. So I decided to put the memory in a wordless box and label it: harmless. If one day, someone asks: What did you see that night? I handed over the box and asked him to take a picture by himself. There was him in the box, as well as paper and lenses. The glass of the camera reflects a face with neither slogans nor smiles on the face, only a pair of eyes – not anger, but awake.

People who wake up don’t necessarily talk. There are only two things to do when you wake up: open the window and turn off the light. When the window is opened, the wind comes in; when the light is turned off, the shadow is not so scary. As for the rest, I dare not think about it or teach it. Teaching people is dangerous, especially in a place where even the wind needs to be filed. That’s it. I wrote this, stopped writing, like the doctor slowly pulled the knife out of the wound. The knife was cold and the blood was hot, and neither of them was satisfied with each other. When they negotiate by themselves, I just hold down the gauze and tell them a few more words: don’t run, don’t cry, don’t watch the excitement. Because people who watch the excitement will sooner or later become the people who are watched in the excitement.

There are no words on the paper, and the words are outside the paper.

If you want to see, look up; if you don’t want to look, bow your head.

Looking up, there is wind, and looking down, there is soil.

Between the two, just enough for a piece of paper to pass.

8月23日 洛杉矶迪士尼音乐厅抗议活动

抗议中共假抗战真卖国 揭露中共统战国军后代真相

8/23迪士尼音乐厅抗议活动

抗议中共假抗战真卖国 揭露中共统战国军后代真相

活动时间:2025年8月23日(周六)18:00

地点:迪士尼音乐厅门口 663 W 2nd St, Los Angeles, CA 90012

主办单位:

洛杉矶民主平台

中国民主党全国委员会

中国民主党全国联合总部

自由钟民主基金会

抗战真相研讨会

一寸河山一寸血,十万青年十万军。1937.7.7—1945.8.15日,中华民国国军浴血奋战,超过365万国军将士伤亡,终于赢得中华民族近代卫国战争的伟大胜利!

烽火连天的八年抗战中,无数国军将士以血肉之躯筑起民族的长城。卢沟桥畔,佟麟阁、赵登禹将军以身殉国;台儿庄城下,数万将士前赴后继;衡阳孤城,十军将士弹尽粮绝,仍坚守到最后一刻。千千万万无名士兵,也在枪林弹雨中留下了青春与生命。这一场伟大的用血肉之躯铸成的卫国战争,开启了中华民国抗战建国新篇章,奠定中华民国联合国五大国之一的新起点。

然而中华民国命途多舛,中共坐山观虎斗,下山摘桃子。趁国民政府八年抗战国力空虚,国军厌战之时,非法窃取民国政权。1949年江山易帜,神州陆沉至今已76年。

如今中共又篡改历史,乔装成抗战中流砥柱。8月23日中共在洛杉矶迪士尼音乐厅举办“《黄河大合唱》”演唱会,邀请300名国军后代参加演唱会,以达到统战目的,迷惑世人。

我们有责任站出来,

抗议中共假抗战真卖国的卑劣行径,揭露中共统战国军后代真相!

活动方式:

游行演讲 抗战歌曲 重读抗战宣言

活动倡议:林劲鹏 活动策划:袁崛

现场负责人:王乃一 活动协调:王中伟

音乐策划&指挥:康余 横幅设计:王中伟 宋佳航

横幅印刷:孙小龙 设备支持:倪世成

对外联络:程虹 媒体文章:程虹 专业摄影:陀先润

August 23rd Los Angeles Disney Concert Hall Protest

Protest against the Communist Party of China’s fake war of resistance and real betrayal of the country, and expose the truth of the descendants of the Communist Party of China’s united war army

8/23 Disney Concert Hall Protest

Protest against the Communist Party of China’s fake war of resistance and real betrayal of the country, and expose the truth of the descendants of the Communist Party of China’s united war army

Activity time: August 23, 2025 (Saturday) 18:00

Location: 663 W 2nd St, Los Angeles, CA 90012 at the entrance of Disney Concert Hall

Organizer:

Los Angeles Democracy Platform

National Committee of the Democratic Party of China

National Joint Headquarters of the Democratic Party of China

Freedom Bell Democracy Foundation

Seminar on the Truth of the War of Resistance

An inch of rivers and mountains, an inch of blood, 100,000 youths and 100,000 troops. 1937.7.7-1945.8.15, the National Army of the Republic of China fought hard, with more than 3.65 million Kuomintang soldiers casualties, and finally won the great victory of the Chinese nation in the modern patriotic war!

During the eight-year war of resistance, countless soldiers built the Great Wall of the nation with their flesh and blood. On the bank of the Lugou Bridge, Generals Tong Linge and Zhao Dengyu were martyred; under the city of Taierzhuang, tens of thousands of soldiers went to succeed; in the lonely city of Hengyang, the soldiers of the ten armies ran out of food and still persevered until the last moment. Thousands of unknown soldiers have also left their youth and lives in the rain of bullets. This great patriotic war, which was cast by flesh and blood, opened a new chapter in the founding of the Republic of China and laid a new starting point for the Republic of China, one of the five major countries of the United Nations.

However, the fate of the Republic of China was sadly. The Communist Party of China sat on the mountain to watch the tiger fight and went down the mountain to pick peaches. Taking advantage of the eight-year anti-war national power of the Kuomintang government, when the national army was tired of war, it illegally stole the power of the Republic of China. In 1949, Jiangshan changed its flag, and it has been 76 years since the land in Shenzhou.

Now the Communist Party of China has tampered with history and disguised as the mainstay of the War of Resistance. On August 23, the Communist Party of China held the “Yellow River Chorus” concert at the Disney Concert Hall in Los Angeles, inviting 300 descendants of the National Army to participate in the concert in order to achieve the purpose of the united front and confuse the world.

It is our responsibility to stand up,

Protest against the despicable behavior of the Communist Party of China pretending to betray the country in the War of Resistance, and expose the truth about the descendants of the Communist Party of China’s army in the United War!

Activity mode:

March speech, anti-war songs, re-reading the anti-war declaration

Activity Initiative: Lin Jinpeng Activity Planning: Yuan Li

On-site person in charge: Wang Naiyi Activity coordination: Wang Zhongwei

Music Planning & Conductor: Kang Yu Banner Design: Wang Zhongwei Song Jiahang

Banner printing: Sun Xiaolong Equipment support: Ni Shicheng

External Contact: Cheng Hong Media Article: Cheng Hong Professional Photography: Tuo Xianrun

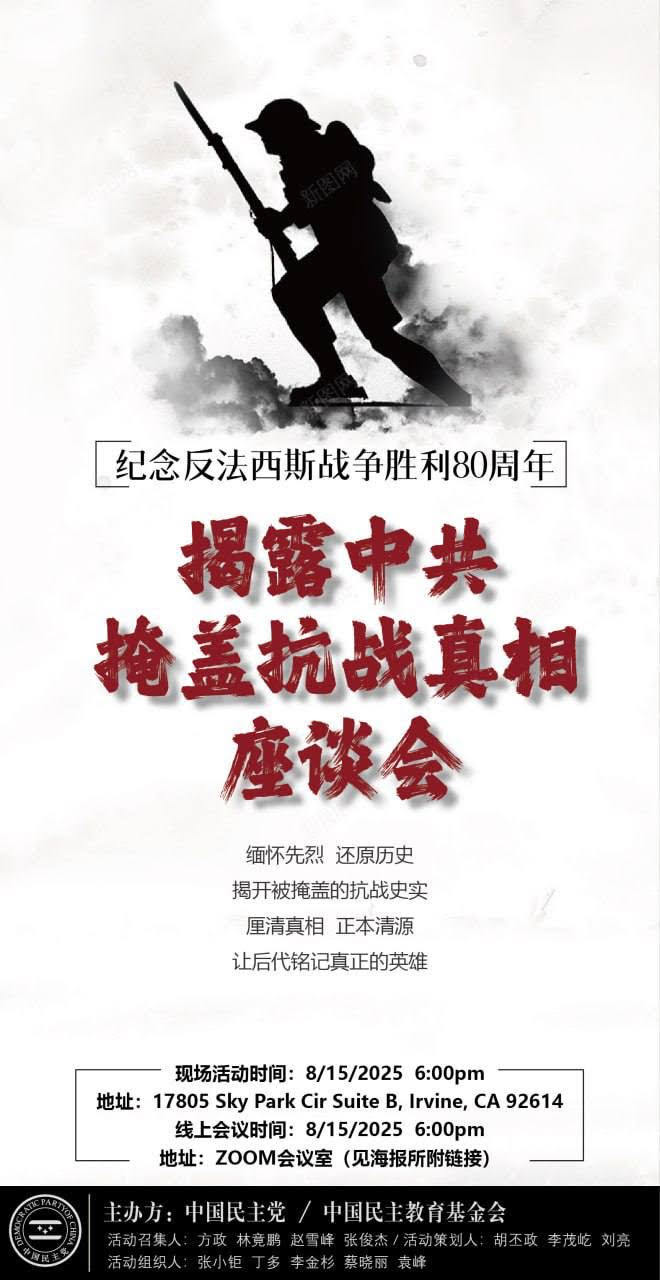

纪念反法西斯胜利 80 周年

——揭露中共抗战历史谎言尔湾座谈会成功举行

作者:赵雪峰

编辑:李聪玲 责任编辑:罗志飞 翻译:程铭

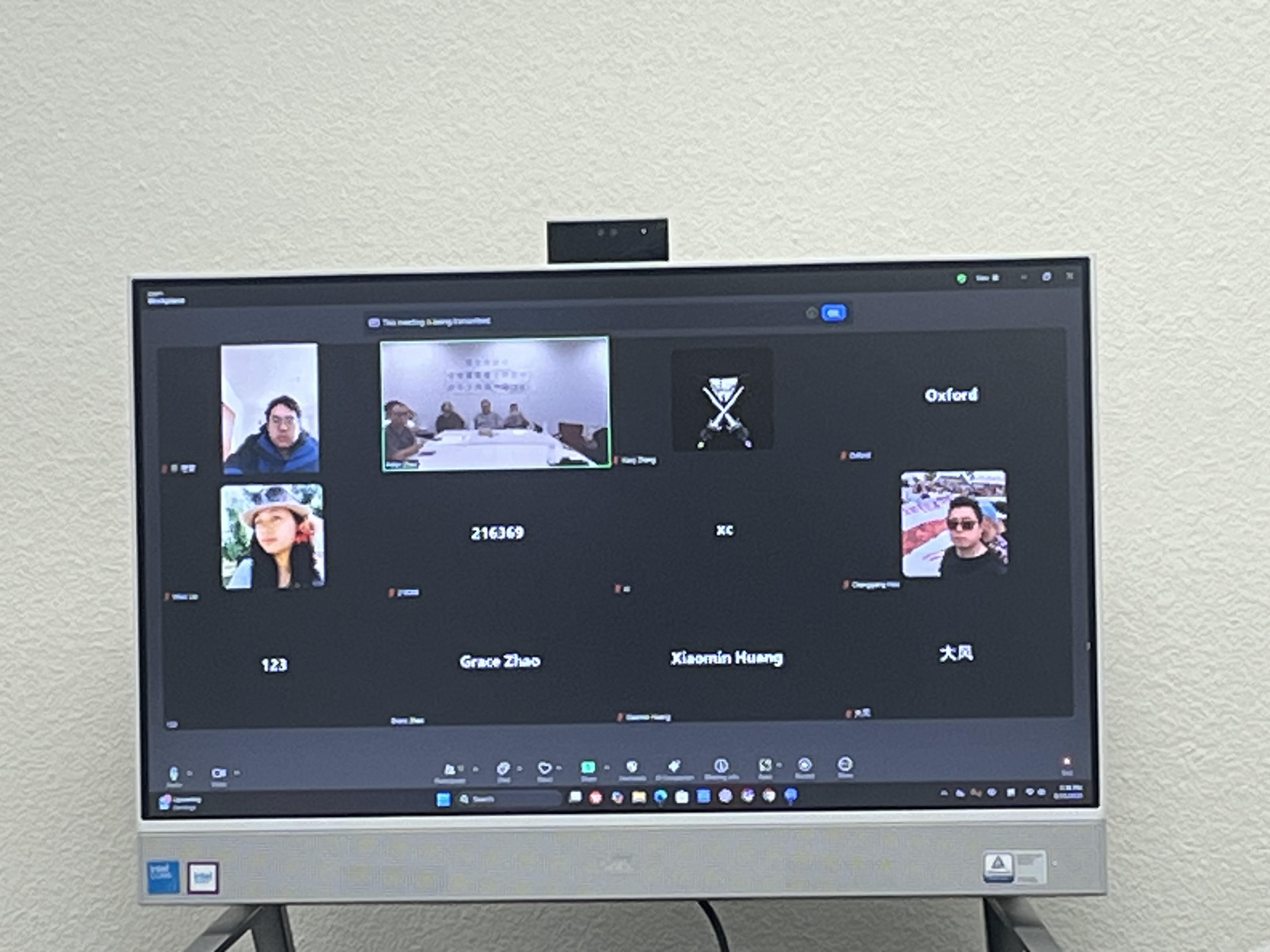

2025 年 8 月 15 日晚,由中国民主党、中国民主教育基金会、洛杉矶中国民主平台联合主办的“纪念反法西斯战争胜利 80 周年”主题座谈会在南加州尔湾成功举行,并通过线上平台与旧金山部分民主人士进行互动交流。

八十年前,全球反法西斯力量经过艰苦卓绝的斗争,赢得了和平与自由。这段历史属于全人类,也铭刻着无数先烈的牺牲与奉献。然而在中国大陆,真实的抗战史却长期遭到中共的歪曲与掩盖。真正的抗战中坚——包括国民政府军队和广大民间抗日志士——在中共的官方叙事中被刻意抹去,取而代之的是中共军队是“中流砥柱”的政治神话。

中国民主党党员、历史学专业的张俊杰在发言中指出:史料显示,国民政府军队在正面战场承担了绝大多数抗战任务,诸如淞沪会战、台儿庄战役、长沙会战等关键战役均取得重大胜利;而中共部队主要集中在敌后开展游击战,以扩大根据地为主要目标,与日军的大规模正面作战极为有限。根据日本官方战史及战后公布的数据,1937 至 1945 年间,日本在中国战场的兵员损失约 200 万至 250 万人(包括阵亡、受伤和失踪)。美国战时驻华军事顾问团与国民政府军事委员会的统计显示,正面战场由国军牵制并歼灭了超过 90% 的日军;美国国家档案馆的战时情报也表明,中共军队直接歼灭的日军不足总伤亡的 5%。台湾“国史馆”的战报进一步揭示,中共在战果上普遍存在夸大现象,例如“百团大战”官方宣称歼敌 2 万余人,但日军战史记载其实际损失不足一半。

曾在中共体制内任职的民主人士袁平表示:“这次纪念活动的意义不仅在于揭露中共篡改抗战史的谎言,更在于唤醒公众对历史真相的追求。一个政权如果能在民族最重要的记忆上造假,它就能在任何领域欺骗人民。守护真实,就是守护未来。”

刚来美国不久的孙圣尧先生则说:“来到国外,我才知道自己学了一堆假历史。中共篡改抗战史,不是学术争论,而是政治操控。它需要一个‘自己拯救了民族’的神话来证明其统治的合法性。这种谎言一旦深入人心,就会让人误以为没有共产党就没有新中国。”

来自旧金山的民运人士张小驹则从更广阔的视角指出:“在西方叙事中,纳粹政权因其迫害与反人类罪行被视为现代史上最邪恶的政治实体。但如果比较中共与纳粹的反人类特征,会发现中共在死亡人数、迫害范围、信息控制和意识形态扩张上,已在多个层面展现出更大的危害潜力。在人工智能与数字监控的助力下,中共的体制性威胁可能成为 21 世纪人类社会面临的最大挑战之一。”

中国民主党党员李金杉强调:“纪念不仅是缅怀,更是守护真相。今天我们重温历史,就是要告诉后人:尊重事实,才能守护尊严;捍卫真实,才是对先烈最好的告慰。”

本次活动召集人、中国民主教育基金会洛杉矶地区项目主管赵雪峰在总结发言中指出:“这不仅是一场纪念,更是一场公民教育。历史真相是民族的集体记忆,如果任由谎言主导,下一代就会在虚假的故事中成长。通过这次座谈,我们希望公众看到被隐藏的史料,认识到国民政府军队和民众才是抗战的主体力量。捍卫历史真实,就是捍卫民族的尊严与未来。”

参加此次座谈的还有雷晶、耿冠军、李茂屹、鲜文君、严黛佳、侯成罡、李贤兵、袁峰、黄晓敏、刘晨、刘妙等二十余位民主人士。

Commemorating the 80th anniversary of the victory of the anti-fascist

——The Irwan Symposium on Exposing the History of the Communist Party of China’s War of Resistance was successfully held.

Abstract: The symposium on “Commemorating the 80th Anniversary of the Victory of the Anti-Fascist War” co-sponsored by the Democratic Party of China, the China Democratic Education Foundation and the Los Angeles China Democracy Platform was successfully held in Irvane, Southern California, and interacted with some democrats in San Francisco through the online platform.

Author: Zhao Xuefeng

Editor: Li Congling Responsible Editor: Luo Zhifei Translator:Ming Cheng

On the evening of August 15, 2025, the symposium on “Commemorating the 80th Anniversary of the Victory of the Anti-Fascist War” co-hosted by the Chinese Democratic Party, the China Democratic Education Foundation and the Los Angeles China Democracy Platform was successfully held in Irvie, Southern California, and some democrats in San Francisco were successfully held through the online platform. Interactive communication.

Eighty years ago, the global anti-fascist forces won peace and freedom after a arduous struggle. This history belongs to all mankind, and it also engraves the sacrifices and dedications of countless martyrs. However, in mainland China, the real history of the War of Resistance has long been distorted and covered up by the Communist Party of China. The real core of the war of resistance – including the army of the national government and the majority of civilian anti-Japanese war – was deliberately erased in the official narrative of the Communist Party of China, replaced by the political myth that the Chinese Communist Party of China’s army is the “mainstay”.

Zhang Junjie, a member of the Democratic Party of China and a history major, pointed out in his speech: historical materials show that the Kuomintang army has undertaken the vast majority of anti-war tasks on the front battlefield, such as the Battle of Song-Shanghai, the Battle of Taierzhuang, the Battle of Changsha and other key battles have achieved major victories; while the Communist Party of China troops mainly concentrated behind the enemy to carry out guerrilla warfare. With the expansion of the base as the main goal, the large-scale head-on battle with the Japanese army is extremely limited. According to Japan’s official war history and post-war data, between 1937 and 1945, Japan lost about 2 million to 2.5 million soldiers on the Chinese battlefield (including dead, wounded and missing). According to the statistics of the U.S. Wartime Military Advisory Corps in China and the Military Commission of the National Government, the front battlefield was restrained by the National Army and annihilated more than 90% of the Japanese soldiers; the wartime intelligence of the U.S. National Archives also shows that the Chinese Communist Party directly annihilated less than 5% of the total casualties of the Japanese army. The war report of Taiwan’s “National History Museum” further revealed that the Communist Party of China’s widespread exaggeration in the results of war. For example, the “Hundred Regiments War” officially claimed to annihilate more than 20,000 enemy men, but the Japanese military history recorded less than half of its actual losses.

Yuan Ping, a democrat who has served in the Communist Party of China, said, “The significance of this commemorative event is not only to expose the lies of the Communist Party of China’s tampering with the history of the War of Resistance, but also to awaken the public’s pursuit of historical truth. If a regime can falscate the most important memory of the nation, it can deceive the people in any field. To protect the truth is to protect the future.

Mr. Sun Shengyao, who had just arrived in the United States, said, “When I came abroad, I realized that I had learned a lot of fake history. The Chinese Communist Party’s tampering with the history of the War of Resistance is not an academic argument, but a political manipulation. It needs a myth that ‘he saved the nation’ to prove the legitimacy of its rule. Once this kind of lie is deeply rooted in people’s hearts, it will make people mistakenly think that there is no new China without the Communist Party.

Zhang Xiaoju, a folk activist from San Francisco, pointed out from a broader perspective: “In Western narratives, the Nazi regime is regarded as the most evil political entity in modern history because of its persecution and crimes against humanity. However, if we compare the anti-human characteristics of the Communist Party of China and the Nazis, it will be found that the Communist Party of China has shown greater harmful potential at multiple levels in terms of the number of deaths, the scope of persecution, information control and ideological expansion. With the help of artificial intelligence and digital monitoring, the institutional threat of the Communist Party of China may become one of the biggest challenges facing human society in the 21st century.

Li Jinshan, a member of the Chinese Democratic Party, emphasized: “Commemoration is not only to remember, but also to protect the truth. Today, we revisit history, which is to tell future people that respecting the facts can protect dignity; defending the truth is the best comfort to the martyrs.

Zhao Xuefeng, the convener of this activity and the project director of the Los Angeles region of the China Foundation for Democratic Education, pointed out in his summary speech: “This is not only a commemoration, but also a civic education. The historical truth is the collective memory of the nation. If it is left to be dominated by lies, the next generation will grow up in false stories. Through this symposium, we hope that the public can see the hidden historical materials and realize that the army and people of the National Government are the main forces of the War of Resistance. To defend the truth of history is to defend the dignity and future of the nation.

More than 20 democrats, including Lei Jing, Geng Champion, Li Maoyi, Xian Wenjun, Yan Daijia, Hou Chenggang, Li Xianbing, Yuan Feng, Huang Xiaomin, Liu Chen and Liu Miao, also participated in this symposium.