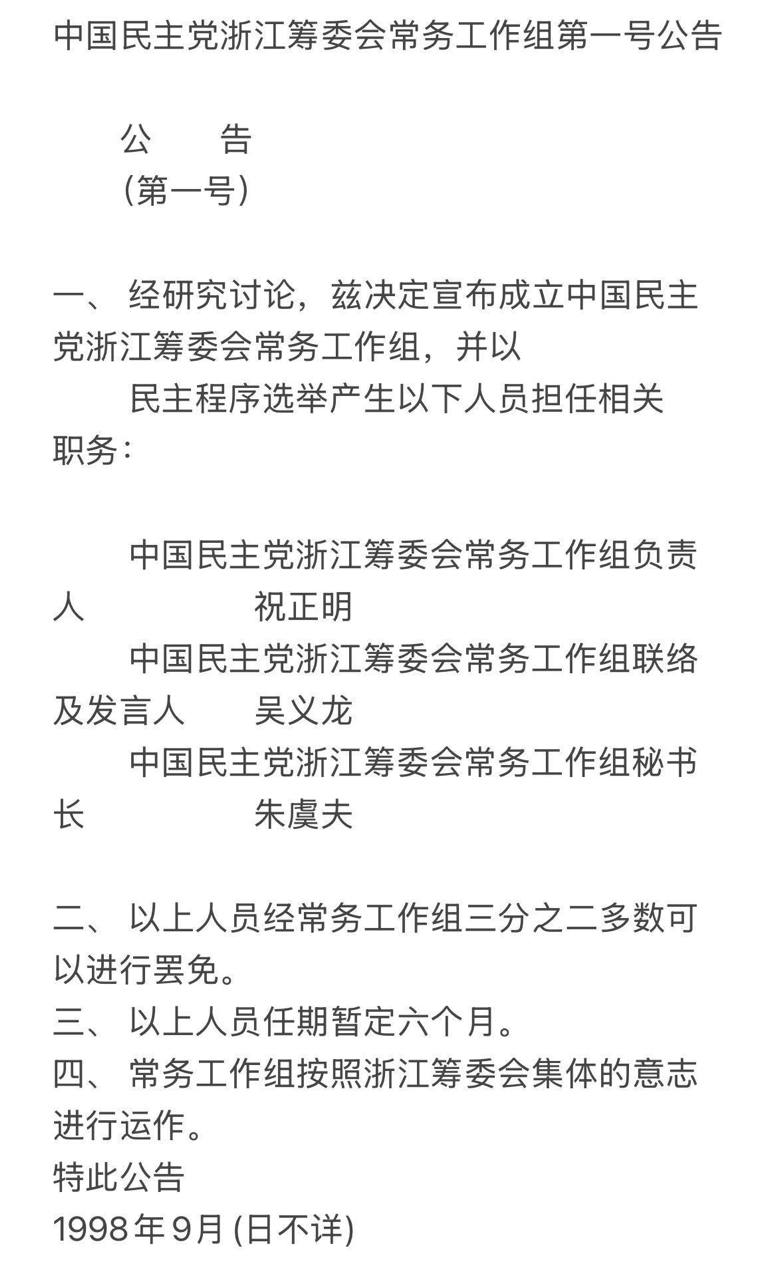

青年首相(二)

“The Rise and Fall of the Sino-Japanese Peace Movement”

Chapter One: The Young Prime Minister (Part Two)

作者:程铭

编辑:冯仍 责任编辑:罗志飞 翻译:鲁慧文

远在1936年10月3日,参谋本部中国课的冈田酉次少佐就在《东洋经济新报》上发表了《支那的统一倾向与对支那之重新认识》一文,揭开了“中国再认识论”的序幕。作为军内不多的经济学家之一,冈田酉次主要从法币的成功发行出发,认为中国正渐渐统一,“分治合作”已沦为一种过时的东西。他说,“蒋政权的确立和统一支那过程的突飞猛进”,不是什么表面而偶然的现象,中国人愿意把自己的银元和银两换为纸币,是中国统一的最好试金石。他认为,“僵化的‘分治合作观点,让许多人无法认识到满洲事变以来,支那领导阶级和知识阶层中根深蒂固的民族意识,(这种意识)构成了蒋政权的强大后盾”。

然而,这篇文章仅昙花一现。冈田后来谈道:“本来预定连载,因文章内容不符合当局的意向……仅发表了绪言部分就作罢了。” 对此,日本学者波多野澄雄却认为:“当时允许部分发表冈田的文章,这表明了,在不得不承认币制改革成功的背景下,陆军内部要求重新研究中国政策的呼声十分强烈。”

而在冈田酉次之后,1937年2月,东京帝国大学教授、著名的基督徒和人道主义者矢内原忠雄发表的《支那问题之所在》一文,却引发了轩然大波。

这篇文章发表在日本最具影响力的政论杂志《中央公论》上。矢内原忠雄认为,无论法币的发行还是西安事变的种种变奏,都表明中国已经统一了。“只有采取认识、承认、援助的政策,才能有助于中国、日本和东南亚的和平” 。对这个观点,满铁调查部的大上末广等人嗤之以鼻。他们谈道,蒋介石之所以能在军阀混战中胜出,是因为他得到了西方国家的支持,“国民党的经济建设只能促使中国进一步沦为英美列强的殖民地”。在这两种泾渭分明的立场出现后,包括岩渊辰雄、绪方竹虎等著名报人和中西功、尾崎庄太郎这样的日本共产党人也加入了论战,并使这场论战为学界所瞩目。

岩渊辰雄既不赞同“统一论”,也不附和“殖民地说”。他反问道,如果中国并未统一、蒋介石只是英美的傀儡,那么,过去几个月中国人生机勃勃的景象从何而来?如果中国已经统一,那么,阎锡山、李宗仁等人会不会允许蒋介石过问他们的内部事务?他由此得出结论,这是一种脆弱的、由共同敌人而促成的表面统一,“一旦失这篇文章刊登在日本最有影响的政论杂志《中央公论》上。去目标,随时可能像沙滩建筑那样轰然倒塌”。而对这个看法,中西功、尾崎庄太郎等人颇不以为然。他们认为,这是以国民党为中心的观点,“推进中国统一的力量基本不是国民政府,而是争取独立民主、走向团结的民族运动”。也就是说,无论国民党会不会再次分裂,中国的统一都是不可避免的……

在这形形色色的见解中,当时最为人接受的,是《朝日新闻》记者、左翼人士尾崎秀实的分析。尾崎秀实谈到,中国的统一,源于蒋介石与四万万民众的一致选择“但国民党政权自身绝没有领导、控制这场民族运动的能力”;在二者合拍时,这个古老民族将焕发出巨大的力量,“(但)稍有不慎,国民党政权就有可能被民族运动潮流冲垮”。这个说法既和岩渊辰雄有相似之处,又接近中西功、尾崎庄太郎等人的观点,一时被视为这场论战的最大收获。

又何止是民间、舆论界?1937年1月,著名外交家佐藤安之助在一份报告里写道:“支那几乎已非昔日之支那,已经成为完全不同的新进国家……他们巧妙地将日本的压迫用于他们的内政,令人惊异的同仇敌忾心和国家思想已经开始抬头。” 次月,具备七年驻华经验的‘中国通’楠木实隆,在《对支政策意见》一文中不仅表达了类似观点,他还有意区分了“支那”和“中国”两个概念。他说:“看中国的现状,虽然反中央各派尚存,但都无法根本颠覆现存之中央政府……分治合作之构想,是只: “““清、日俄战争时代之支那,而不知中国之现状。”换言之,这种认为中国已经新生、“分治合作”不再合乎时宜的观点,在日本政界、军界和知识界都有了为数不少的赞同者。

而这场持续近半年的论战,涵盖多种观点和立场,几乎没有一篇文章受到新闻检查部门的干涉,更没有一个作者受到宪兵、秘密警察的传讯或盘问。因为,那些消息灵通的检查官和特高课人员都早已知道,这场大讨论的幕后人物,是当时权倾朝野、有着惊人实力、时任参谋本部第一部(作战部)部长的石原莞尔少将。

石原莞尔,1889年生,日。” 换言之。作为“满、 “变”、 “作俑者,过去几年,他的形象已渐渐被日本公众、各国舆论所熟知:他粗野、狂妄,是一个不折不扣的战争贩子。十余年前,他在德国留学期间,当美国驻德使馆武官建议他考察美国时,他无比傲慢地回答:“不,我去美国只能有一个身份,那就是日本的美国占领军司令官。” 一时被柏林社交界视为不受欢迎的人物。他又才华横溢、目光远大,并且对众多事物都有着惊人的直觉。他的《战争史大观》、《最终战争论》等几篇文章,无不充斥着一种迷人、邪恶、近乎胡思乱想的天才光芒,因此被誉为‘昭和新军人’的代表、昭和时代第一战略家。在过去的日子里,在此后的几十年,这样毁誉不一、异常极端的评价,始终伴随着他。

但很少有人知道,至迟从1935年开始,他就预感到了日本的战败命运。他认为第二次世界大战将在1940年前后爆发,而日本不仅将卷入这场战争,它还很可能在几年后不可避免地战败、沦亡。作为日本佛教“日莲宗”的狂热信徒,此后一年多,他开始像六百余年前面临蒙古入侵的日莲一样,进行着不知疲倦的鼓与呼、四处奔走游说。

威胁来自苏俄。1933年1月,在遥远的莫斯科,斯大林宣布 “一五计划” 提前完成,大约1500个大型企业投产,在机床、化学、飞机、汽车与拖拉机等工业领域,苏联均已跃居世界的前列;紧接着,他又颁布了雄心勃勃的 “二五计划” ,按照这个计划,1937年苏联将成为仅次于美国的工业强国……凡此种种,都让接受着鲁登道夫的 “总体战” 思想、深刻认识着工业实力和现代战争关系的石原莞尔如坐针毡。

几十年来,日本始终以苏俄为头号大敌。在很大程度上可以说,石原等人的吞并满洲、觊觎内蒙,为的也是获得一个广袤的纵深区,以扭转对苏战略的不利局面。但伴随着苏俄的崛起,征服满洲的勋业顿时显得黯淡无光了。1934年,苏俄开始向远东大举增兵,当年兵力就达到13个师,大约23万人。与此相对比,日本陆军的总兵力也不过23万人,其中在满洲的关东军不过3个师团、1个旅团,兵力不超过5万。次年,这个差距扩大到17个师对3个师团、两个旅团。更要命的是,从这一年起,两国驻军的对抗事件骤然升级了, “仅昭和十年(1935)一年内即达176件之多……超过以往三年只发生的152件,特点是包括有较大规模的武装冲突” 。

及至1936年,远东苏军已成为一股足以毁灭满洲、颠覆东亚的战略力量了。它共有19个师,大约30万人,并装备了1200余辆战车、1200余架飞机以及30艘潜水艇。它不仅在数量上超过了日本陆军,“尤其是它的近代装备,和旧式装备的日本陆军相比,大大地领先了”。更不必说,倘若日苏开战的话,部署在中亚、欧洲的百余万苏军可以沿着西伯利亚铁路迅速前来增援,“估计苏军对日作战的兵力能达到50个狙击师”。日本战史后来记载:“苏联于昭和三年(1928)开始的第一个五年计划,特别着重加强红军的装备……昭和十一年(1936),红军约为160万,到翌年7月华北事变爆发时达到185万的阵势” 。“从远东红军同日本陆军在朝鲜、满洲兵力的增强变化看……出现了无法相比的最坏、最危险的状态,尤其是空军兵力相差更为悬殊”(日本防卫厅,《中国事变陆军作战史》)。

为避免日本的灭顶之灾,1935年8月,石原莞尔回到本土,决心以参谋本部作战课课长的身份改变日本尤其是空军兵力相差更为悬殊” ((((他抵达东京当天,一名叫相泽三郎的陆军中佐闯进陆军省军务局局长永田铁山的办公室,用军刀斩杀了他。石原与永田相交多年、知己知彼,两人并肩拥有 ‘天才’的声誉。永田之死让石原悲痛不已,却意外地让石原成为 “统制派”少壮军官的新领袖。

永田遇刺之后,是“二二六兵变”的爆发、日本前所未有的政治危机。

1936年2月26日凌晨,大雪之夜,千余名 “皇道派” 叛军分九路袭击了众多元老重臣的官邸,并占据了东京永田町、霞关一带的政治中心。自内大臣斋藤实以下,众多大臣已被叛军杀戮,首相冈田启介生死不明,日本已处于彻底的无政府状态。当天下午,石原就以参谋本部作战课课长的身份调集了3个联队、3个步兵大队入京,并包围了叛军。

惊慌失措的天皇得知石原的行动后,又惊又喜又疑惑,他知道石原,却不清楚“石原是个什么样的人”。似乎是要回答天皇的惊疑,2月28日拂晓,在天皇下达24小时最后通牒令后,石原以戒严军参谋长的身份前往叛军的指挥中心山王饭店,勒令叛军缴械投降。当叛军首领之一栗原安秀中尉掏出手枪威胁他时,他也毫不示弱地掏出手枪,与栗原进入了对峙状态。

及至2月29日凌晨,通牒令到达最后时刻,两名“皇道派”首脑真崎甚三郎和荒木贞夫来到戒严指挥部,恳求石原给叛军最后一个机会。“石原毫不客气地把这两个大将赶了出去” (马克-皮蒂,《石原莞尔》)。

几天后,石原就以大佐军衔、课长身份,被任命为平定叛乱后负责整肃陆军的核心人物之一。外挟满洲势力、内靠众多“统制派”少壮军官的拥戴,在长达几个月的“肃军”过程中一举奠定了自己的地位。

1936年6月,参谋本部进行了一次重大改组,设立了战争指导课。 “根据石原大佐的提议,在目前形势下应设置新的有关指导战争的主管课,专门研讨国防国策,这一提议被采纳了。6月上旬……在第一部内设置了主管指导战争和判断形势的 ‘第二课,石原大佐任课长”。而按照新拟定的条例,这个课几乎具有宽泛无边、足以影响日本政治的权力。它可以确定国防战略,“制定指导战争计划的大纲”;它可以干涉政治,“为准备战争策划必要的有关国内改革的具体方案”;它还将上达天听,“拟定向天皇启奏的大纲和执行天皇亲裁的军事布局等事项”。(日本防卫厅,《中国事变战争指导史》)

又何止于此?日本宪法规定,宣战、媾和的大权属于天皇,但在君主立宪制的政体下,天皇一般不会轻易驳斥主管部门的意见。这么一来,作为襄赞战和大事的唯一机关,石原就拥有了决定战和的最大发言权。而在此之外,次年3月,他又以少将军衔升任分管战争指导课、作战课和国土防卫课的第一部(作战部)部长,从而成为参谋本部一言九鼎的人物,将参谋本部九成以上的权限集中在自己手里。

然后,是日本战略的重新确定、各种国策的改弦易辙。

这一系列战略与国策,皆以应对苏俄为核心目标。也是1936年6月,在石原的建议下,“日德防共协定”谈判开始了。尽管众多大臣对刚刚武装起来的德国究竟有多少实力心怀疑虑,尽管“最后一名元老”、时年87岁的西园寺公望明确反对这个协定,当年11月25日,这个协定还是达成了。日本战史后来谈道,此举是为了争取时间,“寄望德国的复兴,将苏联牵制在欧洲”。

后来的历史表明,这几乎是当时日本作出的最明智、最有意义的一个决策。此后九年,尽管日本陷入了中日战争的泥潭,尽管希特勒决定先对西欧动手,但在纳粹德国赫赫武功的威慑下,苏俄始终不敢越雷池一步,直到德国战败、美国也在广岛投下第一颗原子弹后才对日宣战。

这个战略守势,不仅对苏俄,更针对英美。6月10日,与设立战争指导课、开始 “日德防共协定” 谈判几乎同时,石原起草了一份《国防国策大纲》。明确规定,在对苏战争尚无把握之前,日本将以忍辱负重、卧薪尝胆的精神对苏俄退避三舍。 “即使军备已充实,而且战争准备已接近完善,也应为使苏联放弃在远东采取攻势的政策,而开始积极的工作”。与此同时,日本将尽全力改善与西方特别是美国的关系,“在作长期战争准备还存在极大缺点的今天,如果不去保持和英美,最低限度和美国的友好关系,就难以进行对苏战争” 。

也就是说,从此以后日本将只有苏俄一个敌人,并且绝不主动挑起战争,以便将这股祸水引向西方。而在日德结盟、战略守势之外,则是为期五年的重整军备计划。11月26日,石原制定了《军备充实计划大纲》,决心用五年时间使陆军拥有50个师团,大约150万人的动员能力,并将空军从54个中队扩编为142个中队。 “根据这一设想,在大陆的兵力保持80%,是为了对付苏联的”。而为了实现这个目标,从1937年起,日本的军费预算必须从原本的7亿余元猛增到14亿元以上。为确保这个预算的通过,石原还考虑撤换掉 “二二六兵变”后上台的广田弘毅首相,换上一个更听话的、最好是陆军出身的傀儡;不久后,以众议院议员浅原健三为中间人,他的两个代表与退役陆军大将林铳十郎开始了组阁秘密谈判……

就在如此千头万绪、百废待举的局势中,1936年渐渐走到尽头了。石原认为,依靠日德结盟、战略守势和重整军备,依靠自己的手握战和大权并交好英美,日本或许能避免过早地与苏俄决战,并避免未来的灭顶之灾。但,恰恰是在这个时候,他听到了“西安事变”的消息,并预感到中日之间很可能爆发一场全面战争。他决心避免这场战争,避免自己的前功尽弃,并避免日本的最终沦亡。

日本战史后来记载:“参谋本部第二课长石原大佐于昭和十一年(1936)年底视察了华北,看到中国反对内战、要求国内统一的趋势越来越高……根据所见,对过去的对华政策再次进行了研究。” (日本防卫厅,《中国事变陆军作战史》)

在“西安事变”之前,改变对华政策并没有进入石原的视野。1936年1月13日,也就是土肥原贤二领衔的 “华北自治” 渐入高潮时,日本政府制定了《处理华北纲要》。这份文件明确了分离华北的先后步骤:首先是实现冀东22县、察哈尔3县的傀儡化, “坚持冀东自治政府的独立性” ;紧接着, “逐步完成冀察两省及平津两市的自治” ;而在做完这一切之后, “进而使其他三省自然地与之合流” 。对此,时任参谋本部作战课课长的石原莞尔并没有什么反对意见,他只是告诫说, “在这一时期,对外要慎重从事,不招惹是非至为重要” 。

而在确定战略守势并交好英美后,1936年8月11日,日本政府又决定一方面拉拢中国加入反苏同盟,另一方面加快华北五省的分离工作,为此抛出了《对中国实施的策略》和《第二次处理华北纲要》。但石原同样没有觉察这二者之间的矛盾,他仅仅建议,为避免让中国感到更大的威胁,“对于其他地方政权,不特别采取措施帮助或阻止中国的统一和分裂”。

直到当年9月15日,当参谋本部制定《对华时局的对策》,提出在华中、华南采取克制态度,而在华北不惜使用武力时,石原也只是再三强调,“对华全面作战就会是持久的消耗战,应该绝对避免。就准备对苏作战而言,即使对华局部地区作战,都应该极力回避”(日本防卫厅,《中国事变陆军作战史》)。

但“西安事变”爆发后,一切都不一样了。石原认识到,无论华中、华南还是华北,对中国任何一个区域的作战,都意味着全面战争。日本将面对的,不仅是当地军阀,还有那个已经统一的中国,无比广袤的江山和多达四万万的民众。为此,1937年1月6日,几乎刚刚结束了对华北的视察,他就提出要修改对华政策。他不仅决心停止分离华北,他还放弃了将中国视为经济殖民地的企图。他的主张体现在修改后的《对中国实施的策略》以及《第三次处理华北纲要》里。《剑桥中华民国史》后来写道:“这两个文件强调用 ‘文化和经济的手段以实现两国的‘共存共荣,并需要‘同情地看待南京政府统一中国的努力。会议决定不再谋求华北自治或促进分裂工作,地方政权不再受到支持来鼓励分裂,相反,日本将试图在全中国造成一种互相信任的气氛……这是一个惊人的政策转变,也是对军方肆无忌惮的扩张战术失败的一次坦率的承认。”

又何止于此?此后几个月,石原还发出一个个信号、派出一个个使团,以避免中日关系的恶化。2月2日,在他的操纵下,林铳十郎内阁成立了。当天林铳十郎就在众议院发表演说: “日华关系除政府之外,还将扩大民间接触,配合两国国民的感情,使邦交明朗化,以共同实现东亚安定。”3月9日,佐藤尚武接任外相,他在贵族院公开谈道: “将从两国平等的立场出发,重新进行日华交涉……(将)正确认识正在加强统一的国民政府的力量,并尊重其统一。” 而在内阁之外,3月12日,以日本国家银行总裁、日华贸易协会会长儿玉谦次为团长,一个高规格的日本经济使节团来到上海, “会见了蒋介石和中国要人以及经济界人士,至26日为止进行了几次会谈”。与此同时,石原也发起了那场 “中国再认识”的讨论,试图让更多的日本人改变对华观感。甚至,在这个过程中,他还考虑取消 “冀东自治政府”,以表达对日华和平的诚意。

然而,一切已为时已晚。这一年7月7日,在北平西南郊的宛平城边,“卢沟桥事变”爆发了。

“The Rise and Fall of the Sino-Japanese Peace Movement”

Chapter One: The Young Prime Minister (Part Two)

Author: Cheng Ming

Editor: Feng Reng

Chief Editor: Luo Zhifei

Translated by: Lu Huiwen

Abstract:

This section, by tracing the fierce debates within Japan’s political, academic, and military circles from 1936 to 1937 over the question of “whether China had already achieved national unification,” reveals the cognitive divergences and strategic contestations underlying the evolution of Sino-Japanese relations. The article focuses on how the intellectual trend of “Reassessing China” emerged and how Major General Ishiwara Kanji played a key role behind the scenes in promoting this discourse to influence the direction of Japan’s China policy.

The piece also offers a detailed analysis of Ishiwara’s deep concerns over the Soviet threat and his leadership in formulating strategic concepts such as “strategic defense posture,” “the Japan-Germany Anti-Comintern alliance,” and “a policy of moderation toward China.” These policy frameworks illustrate the complex tug-of-war and unfinished efforts within Japan on the eve of full-scale war.

The entire chapter is logically structured and grounded in solid historical sources, presenting a vivid intellectual landscape and strategic turning point just before the outbreak of war.

As Early as October 3, 1936, Major Okada Yuji from the China Section of the Japanese Army General Staff published an article titled “China’s Unification Trend and the Need to Reassess China” in the Toyo Keizai Shimpo (Oriental Economic Weekly), thus opening the curtain on the “Reassessment of China” discourse. As one of the few economists in the military, Okada began by focusing on the successful issuance of the national currency (fabi), asserting that China was gradually achieving unification and that the idea of “cooperative division and rule” was now outdated.

He wrote:

“The establishment of the Chiang Kai-shek regime and the rapid progress of China’s unification are not superficial or accidental. The Chinese people’s willingness to exchange their silver dollars and bullion for paper money is the best litmus test for unification.”

He argued that the outdated “cooperative division” viewpoint prevented many from recognizing the deeply rooted national consciousness among China’s elites and intellectuals since the Manchurian Incident—this consciousness, he believed, was the backbone of Chiang’s regime.

However, the article appeared only briefly. Okada later reflected:

“It was originally planned as a serialized piece, but since the content did not align with the government’s wishes, only the introduction was published before it was canceled.”

Japanese scholar Hatano Sumio, however, believed:

“The fact that part of Okada’s article was allowed to be published shows that, in the context of having to acknowledge the success of China’s currency reform, there were strong voices within the army calling for a reassessment of China policy.”

Following Okada’s piece, in February 1937, Yanaihara Tadao, a professor at Tokyo Imperial University and a renowned Christian and humanitarian, published an article titled “The Essence of the China Problem”, which sparked a storm of debate.

This article appeared in Chuo Koron, Japan’s most influential political commentary magazine. Yanaihara argued that both the issuance of fabi and the developments of the Xi’an Incident indicated that China was already unified:

“Only a policy of understanding, recognition, and support can contribute to peace in China, Japan, and Southeast Asia.”

This view was ridiculed by figures like Ōue Suehiro of the South Manchuria Railway’s Research Division. They claimed that Chiang Kai-shek’s victory in the warlord era was due solely to support from the Western powers, and that:

“The Kuomintang’s economic development would only further reduce China to a British and American colony.”

As these two starkly opposing positions emerged, others such as renowned journalists Iwabuchi Tatsuo and Ogata Taketora, and left-wing intellectuals like Nakazawa Isamu and Ozaki Shotarō, also joined the debate, drawing significant attention from academia.

Iwabuchi Tatsuo rejected both the “unification theory” and the “colonialism argument.” He posed rhetorical questions: If China wasn’t unified and Chiang was merely a puppet of the West, where had all the vibrancy and vitality in Chinese society over the past few months come from? Conversely, if China was indeed unified, would warlords like Yan Xishan or Li Zongren really allow Chiang to interfere in their internal affairs?

He concluded that China’s unification was fragile and superficial—merely a result of confronting a common enemy:

“Once that goal disappears, the structure may collapse like a castle of sand.”

This view was not accepted by Nakazawa Isamu or Ozaki Shotarō, who believed Iwabuchi’s assessment was too Kuomintang-centric. They argued that:

“The force pushing for Chinese unification does not lie in the Nationalist Government, but in the broader national movement for independence and democracy.”

In their view, regardless of whether the Kuomintang fragmented again, China’s unification was inevitable.

Among this array of views, the analysis by Ozaki Hotsumi—a left-wing journalist at the Asahi Shimbun—was perhaps the most widely accepted. Ozaki wrote that China’s unification resulted from a mutual choice by Chiang Kai-shek and the country’s 400 million citizens. However,

“The Kuomintang regime itself lacks the capacity to lead or control this national movement. When the two forces are aligned, the ancient Chinese nation unleashes immense power. But with the slightest misstep, the national movement may overwhelm the Kuomintang regime.”

His argument blended Iwabuchi’s concerns with the optimism of Nakazawa and Ozaki Shotarō and came to be regarded as the most insightful contribution to the debate.

Nor was this debate limited to public opinion and civil society. In January 1937, the renowned diplomat Satō An’nosuke wrote in a report:

“China is no longer the China of old—it has become a completely new, modernizing nation… They have cleverly used Japan’s pressure for their own domestic unification. A surprising surge of national unity and political consciousness is on the rise.”

The following month, Kusunoki Jitsutaka, a “China hand” with seven years of experience in China, expressed a similar view in his piece “Opinions on China Policy.” He even proposed a conceptual distinction between “Shina” and “China.”

He wrote:

“Looking at China’s current state, while anti-centralist forces remain, they no longer pose a fundamental threat to the existing central government… The concept of cooperative division is suited only to the China of the Qing or the Russo-Japanese War era. It does not reflect the reality of China today.”

In other words, by early 1937, the view that China was being reborn and that the old ‘divide-and-rule’ approach was obsolete had gained considerable support across Japan’s political, military, and intellectual elites.

This public debate, which lasted nearly six months and encompassed diverse views and stances, saw almost no censorship or police suppression. None of the writers were summoned by the secret police or military police. Why? Because those in the know—government censors and special higher police officials—were well aware that the man behind this massive debate was none other than Major General Ishiwara Kanji, then Director of the First Department (Operations) of the Army General Staff, and a man of immense political influence.

Ishiwara Kanji, born in 1889, had by then become well known to both the Japanese public and the international press as the mastermind of the Manchurian Incident and the architect of Japan’s aggressive expansion in Asia. He was often described as crude, arrogant, and a warmonger.

A decade earlier, during his studies in Germany, when a U.S. military attaché suggested he visit the United States, Ishiwara arrogantly replied:

“No, the only identity with which I would go to America is as the Commander of the Japanese Occupation Forces.”

He was immediately shunned by Berlin’s diplomatic society.

Yet he was also brilliant, far-sighted, and possessed an uncanny strategic intuition. His writings, such as A Grand View of Military History and On Final War, dazzled readers with their genius, danger, and wild imagination. He was hailed as a representative of the “Shōwa New Military Man” and the greatest strategic thinker of his generation. Throughout his life, and long after his death, he remained a polarizing figure—a man both reviled and revered.

Few people knew that as early as 1935, Ishiwara had already foreseen Japan’s eventual defeat.

He believed that a second world war would break out around 1940, and that Japan would not only be dragged into it but would almost certainly lose.

As a devout follower of Nichiren Buddhism, Ishiwara saw himself as a spiritual successor to Nichiren, who had warned the Japanese government about the Mongol invasion 600 years earlier. For the next year, Ishiwara threw himself into tireless warnings and lobbying efforts, traveling widely to persuade Japan’s elites to change course.

His primary concern was the Soviet Union.

In January 1933, Stalin had declared the First Five-Year Plan completed ahead of schedule, with about 1,500 large-scale enterprises put into operation. In key industrial areas such as machine tools, chemicals, aircraft, automobiles, and tractors, the Soviet Union had leapt into the global lead.

He soon launched the Second Five-Year Plan, with the goal of making the USSR the world’s second-largest industrial power after the United States by 1937.

To Ishiwara—deeply influenced by Ludendorff’s concept of total war and acutely aware of the relationship between industrial power and modern warfare—this was deeply alarming.

For decades, Japan had regarded the Soviet Union as its chief enemy. In many ways, Ishiwara’s drive to seize Manchuria and eye Inner Mongolia was about securing strategic depth to counter the USSR. But as Soviet power surged, the strategic value of conquering Manchuria seemed suddenly diminished.

In 1934, the Soviet Union began large-scale troop deployments in the Far East. By year’s end, it had 13 divisions stationed there—about 230,000 troops. In contrast, Japan’s total army strength was also around 230,000, but its Kwantung Army in Manchuria had only 3 divisions and 1 brigade, totaling fewer than 50,000 soldiers.

In 1935, the gap widened to 17 Soviet divisions versus 3 Japanese divisions and 2 brigades. Even more concerning, the number of military confrontations between the two sides surged, with 176 incidents reported in 1935 alone, exceeding the total of 152 incidents in the previous three years. Some of these were large-scale armed clashes.

By 1936, the Soviet Far East Army had become a formidable force capable of destroying Manchuria and overturning East Asia’s balance of power. It boasted 19 divisions, about 300,000 troops, equipped with over 1,200 tanks, 1,200 aircraft, and 30 submarines.

Not only did this force vastly outnumber Japan’s, but its modern equipment far outclassed the outdated gear of the Japanese army.

And if war broke out, over a million Soviet troops stationed in Central Asia and Europe could be rapidly deployed via the Trans-Siberian Railway, bringing the estimated total Soviet force against Japan to 50 divisions.

Japan’s military history later recorded:

“Since the start of the First Five-Year Plan in 1928, the Soviet Union had focused heavily on strengthening the Red Army’s equipment… In 1936, the Red Army numbered around 1.6 million troops, and by July 1937—when the North China Incident broke out—this had risen to 1.85 million.”

“Judging from the increases in Soviet and Japanese troop strength in Korea and Manchuria, the imbalance reached an unprecedented and dangerous state. The gap in air power was particularly vast How Could It End There?

According to the Japanese Constitution, the powers to declare war and make peace belonged to the Emperor. However, in the political structure of a constitutional monarchy, the Emperor would generally not easily overrule the opinions of the responsible departments. In this context, as the sole organ assisting in decisions of war and peace, Ishiwara Kanji held the greatest voice in deciding such matters.

Moreover, in March of the following year, he was promoted to Major General and appointed as the Director of the First Department (Operations Department), which oversaw the War Planning Section, the Operations Section, and the National Defense Section. With this, Ishiwara became the dominant figure within the Army General Staff Office, concentrating over 90% of the Office’s authority in his own hands.

What followed was a redefinition of Japan’s strategy and a complete shift in its national policies.

This series of strategies and policies all centered on responding to the Soviet Union. In June 1936, under Ishiwara’s recommendation, negotiations for the Anti-Comintern Pact between Japan and Germany began. Despite many ministers expressing doubts about how much actual strength the newly rearmed Germany possessed, and despite explicit opposition from the “last Genrō,” the 87-year-old Saionji Kinmochi, the pact was still signed on November 25 that year. Japanese war history would later state that this move was meant to buy time, “in the hope that Germany’s resurgence would keep the Soviet Union occupied in Europe.”

Subsequent history proved that this was perhaps the wisest and most meaningful decision Japan made at the time. Over the next nine years, even though Japan became mired in the quagmire of the Second Sino-Japanese War, and even though Hitler decided to strike Western Europe first, the formidable military might of Nazi Germany served as a deterrent—the Soviet Union did not dare cross the line until after Germany’s defeat and after the United States dropped the first atomic bomb on Hiroshima, at which point the Soviets declared war on Japan.

This strategic defensive posture targeted not only the Soviet Union, but also Britain and the United States. On June 10, almost simultaneously with the establishment of the War Planning Section and the beginning of negotiations on the Anti-Comintern Pact, Ishiwara drafted the National Defense Policy Outline. It clearly stipulated that until Japan had full confidence in waging war against the Soviet Union, the country would endure humiliation and hardship and retreat as necessary:

“Even if military preparations are complete and war readiness is nearly perfect, we must first work actively to cause the Soviet Union to abandon its aggressive policies in the Far East.”

At the same time, Japan would do everything possible to improve relations with the West, especially the United States:

“Given that our preparations for a long-term war are still gravely deficient, unless we maintain friendly relations—at the very least—with the United States and Britain, it will be difficult to wage war against the Soviet Union.”

In other words, from that point forward, the Soviet Union would be Japan’s only enemy, and Japan would not proactively provoke war—hoping instead to divert the flames of conflict toward the West.

Beyond the Japan-Germany alliance and the strategy of restraint, a five-year military expansion plan was also launched. On November 26, Ishiwara formulated the Outline for Military Expansion, declaring his intention to, within five years, expand the army to 50 divisions with a mobilization capacity of approximately 1.5 million troops, and to expand the air force from 54 squadrons to 142:

“According to this vision, keeping 80% of our forces stationed on the continent is intended to deal with the Soviet Union.”

To realize this objective, starting from 1937, Japan’s military budget would have to increase drastically—from a little over 700 million yen to more than 1.4 billion yen. To ensure that this budget would pass, Ishiwara even considered removing Prime Minister Hirota Kōki, who had taken office after the February 26 Incident, and replacing him with a more obedient puppet—ideally someone from the army. Soon thereafter, through the House of Representatives member Asahara Kenzo as a middleman, two of Ishiwara’s emissaries began secret cabinet formation talks with retired Army General Hayashi Senjūrō.

Amid this chaotic and unfinished state of affairs, 1936 came to an end. Ishiwara believed that by relying on the Japan-Germany alliance, a defensive strategy, and military reorganization—and through his control over decisions of war and peace and improved relations with Britain and the U.S.—Japan might avoid prematurely clashing with the Soviet Union and stave off eventual catastrophe.

But just at that moment, he received news of the Xi’an Incident, and sensed that a full-scale war between China and Japan was highly likely. He resolved to prevent this war, to prevent all his previous efforts from being wasted, and to prevent Japan’s ultimate downfall.

Japanese war history later recorded:

“In late 1936, Colonel Ishiwara, Chief of the Second Section of the General Staff, inspected North China. Observing the growing trend of opposition to civil war and calls for national unification in China… he re-examined Japan’s previous China policy.”

(Japanese Defense Agency, “Army Operations in the China Incident”)

Before the Xi’an Incident, changing the China policy had not even entered Ishiwara’s thinking. On January 13, 1936, as Itagaki Seishirō’s promotion of “North China Autonomy” was reaching its peak, the Japanese government formulated the Outline for Handling North China. This document detailed a phased strategy for separating North China:

First, puppet regimes in the 22 counties of eastern Hebei and 3 counties in Chahar:

“Insist on the independence of the East Hebei Autonomous Government.”

Then,

“Gradually achieve autonomy for Hebei and Chahar provinces and the cities of Peking and Tianjin.”

Finally,

“Naturally bring the other three provinces into union with them.”

At that time, Ishiwara Kanji, as Chief of the Operations Section, expressed no objections. He only cautioned:

“In this period, we must act cautiously in foreign affairs and avoid provoking trouble.”

After the strategy of defensive posture and rapprochement with Britain and the U.S. was set, on August 11, 1936, the Japanese government again decided—on one hand—to woo China into the Anti-Comintern alliance, and on the other, to accelerate the separation of the five North China provinces. It released two more documents: Strategy Toward China and the Second Outline for Handling North China.

But Ishiwara again failed to notice the contradiction between these two goals. He merely suggested:

“To avoid creating greater threats to China, no special measures should be taken to support or oppose the unification or division of local regimes.”

Even on September 15, when the General Staff Office drafted the Countermeasures for the Chinese Situation, proposing a restrained attitude in central and southern China but the possible use of force in the north, Ishiwara only emphasized repeatedly:

“A full-scale war with China would become a prolonged war of attrition and must be absolutely avoided. For the sake of preparing for war with the Soviet Union, even local conflicts in China should be avoided to the utmost.”

(Japanese Defense Agency, “Army Operations in the China Incident”)

But after the Xi’an Incident, everything changed.

Ishiwara realized that military operations in any part of China—whether North, Central, or South—would lead to full-scale war. Japan would not only be facing regional warlords, but also a now-unified China, with its vast territory and a population of 400 million.

Therefore, on January 6, 1937, almost immediately after finishing his inspection of North China, Ishiwara proposed revising Japan’s China policy. He resolved not only to cease efforts to split off North China, but also to abandon any intention of making China an economic colony.

His proposals were reflected in the revised Strategy Toward China and the Third Outline for Handling North China.

The Cambridge History of the Republic of China later wrote:

“These two documents emphasized the use of ‘cultural and economic means to achieve mutual prosperity between the two nations,’ and urged that Japan ‘sympathetically regard the Nanjing government’s efforts to unify China.’ The meeting decided not to pursue North China’s autonomy or to encourage separatist activities. Local regimes would no longer receive support to promote division. On the contrary, Japan would strive to foster an atmosphere of mutual trust throughout all of China… This marked a startling policy shift and a candid admission of the failure of the military’s unchecked expansionist tactics.”

But it didn’t end there.

Over the next several months, Ishiwara continued to send signals and dispatch delegations in an effort to prevent the deterioration of Sino-Japanese relations. On February 2, under his orchestration, the Hayashi Senjūrō Cabinet was formed. That same day, Hayashi declared in the House of Representatives:

“Beyond governmental ties, Japan-China relations will be expanded through private-sector engagement, to foster goodwill among the peoples of both nations and clarify diplomatic ties, thereby jointly achieving peace in East Asia.”

On March 9, Satō Naotake became foreign minister and stated before the House of Peers:

“We will restart Japan-China negotiations from a position of equality… (We will) correctly recognize the growing strength of the Nationalist government and respect its unification efforts.”

Outside the Cabinet, on March 12, a high-level Japanese economic delegation led by Kodama Kenji, President of the Bank of Japan and Chair of the Japan-China Trade Association, arrived in Shanghai:

“They met with Chiang Kai-shek, prominent Chinese officials, and figures in the business world. Several meetings were held through March 26.”

At the same time, Ishiwara launched a ‘Reassessment of China’ campaign, attempting to change Japanese public perceptions of China. At one point, he even considered dismantling the East Hebei Autonomous Government to demonstrate Japan’s sincerity in pursuing peace with China.

However, it was already too late.

On July 7, 1937, near Wanping Fortress southwest of Beiping, the Marco Polo Bridge Incident erupted.

-rId2-1280X960.jpeg?w=696&resize=696,0&ssl=1)

-rId2-1280X960.jpeg)

-rId3-960X1280.jpeg)